Here's What Happened When I Drove 500 Miles To Pick Up A Free Car

Unable to resist the lure of a free Jeep Cherokee, I drove to Columbus, Ohio this weekend to meet up with a totally random reader.

Unable to resist the lure of a free Jeep Cherokee, I drove to Columbus, Ohio this weekend to meet up with a totally random reader who—I was convinced—had plans to harvest my organs. Now I've returned from my trip, and while I didn't have to endure horrifying surgery from a crackhead with a rusty steak knife, I also didn't come back with a free Jeep.

A random reader named Matt Calhoun sent me an email in March offering his beloved first car—a 1992 Jeep Cherokee Briarwood—for dirt cheap, as it had developed an engine knock that he, a college student, couldn't afford to fix. I politely declined. Then a few months passed; nobody would buy the broken Jeep, so Matt said I could have it for free.

Though I had some reservations about taking a free Jeep from some random interneter, there was no way in hell I could turn down four-liters worth of inline-six goodness, even if it did have a knock. So I hit the road and started on my 250 mile trek from Troy, Michigan, to Columbus in my red Jeep filled with tools.

I not only brought two socket sets and a full toolbox, I also brought along two spare rod bearings, some lifters, some rocker arms, and a couple of pushrods—all from my blown up Jeep engine. Clearly, I was ready to drop that oil pan and fix the crap out of Matt's Jeep's engine knock, even if it took me all weekend.

Once my friend Brandon and I finally arrived in Columbus, we jump-started Matt's decrepit Jeep (which had clearly been sitting outside of his apartment for months), only to hear a horrible metal-to-metal noise that is almost definitely what the fieriest pits of hell sound like:

As you can see in the clip above, the first thing Brandon and I did was take off the valve cover to see if any of the pushrods had bent, or if the rocker arms had somehow come loose. But the top end looked in tip-top shape.

We ran a compression test on cylinder one and found only 60 PSI. Between that and the most oil-soaked air filter I had ever seen, I was tempted to say there was an issue in the cylinders. But O'Reilly's compression gauges are notoriously unreliable, and 4.0-liter engines are known to spew oil into their filters, especially when crank case ventilation hoses get clogged. Plus, worn down cylinder walls didn't explain the noise, so I moved on to inspect the bottom end.

Before dropping the oil pan, I wanted to check one of the Jeep Cherokee XJ's achilles heels: the flex plate bolts holding the torque converter to the engine (they're notorious for backing out).

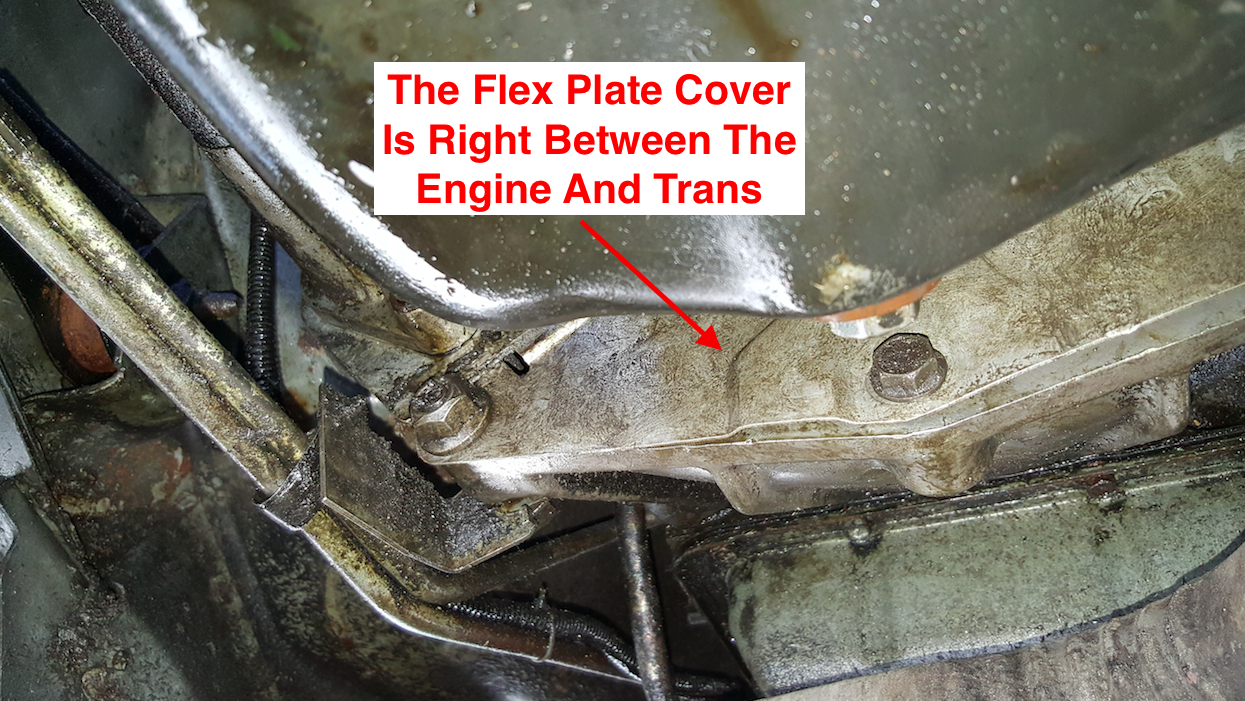

To do that, I had to crawl in the tight spot between the Stock Ride Height Jeep With A Flat Tire and sharp, jagged gravel mixed with glass from the windows a robber had broken out of Matt's old Buick (a Craigslist purchase that he ended up flipping). While squeezed under the oil-covered Jeep, I unbolted and cut a little sheetmetal flex plate cover to gain access to the bolts.

Here's a look at the flex plate cover:

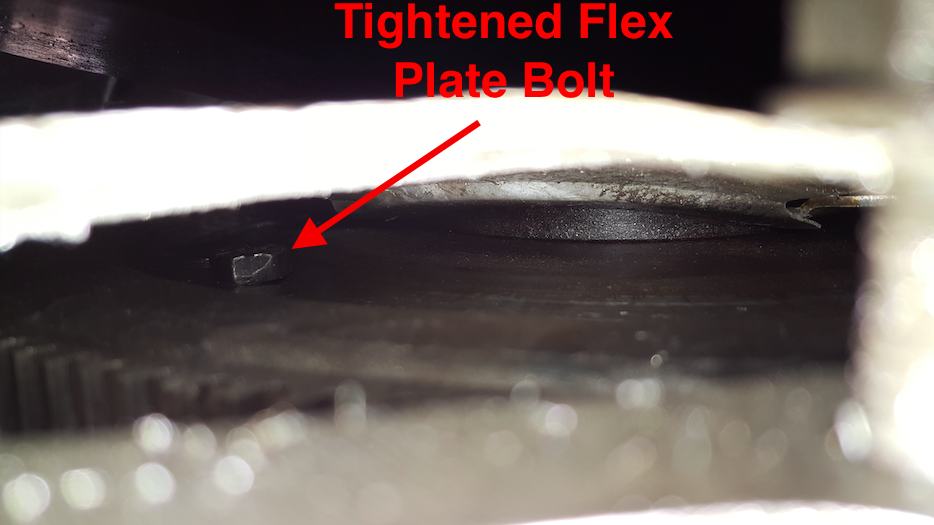

As soon I removed the shield, three flex plate bolts came pouring out onto my face; after Brandon turned the engine over by hand, the fourth and final one fell out, too. We had discovered at least one source of the engine's horrible noise: the motor—no longer connected to the transmission—was rubbing its flex plate against the back of the stationary torque converter while the bolts were being crushed between the plate and the bell housing.

After crashing on Matt's couch, the next morning Brandon and I cleaned up the bolts' marred threads with a rented thread chaser, Brandon turned the engine over until the flex plate holes lined up with the torque converter holes, and I threaded all four bolts in with a bit of loctite to prevent them from popping out ever again.

Then we fired her up:

After a bit of noise from the top end as the thick oil Matt had been using to quell the "knock" made its way to the valvetrain, the Jeep idled like a dream. Coolant temperature remained steady at 210, and oil pressure stuck around 20 psi. This was a healthy four-liter.

And it wasn't just the engine that was in good shape, the transmission shifted perfectly, the suspension was nice and soft, and the steering—whose parts Matt had recently replaced—was excellent. The Jeep was ready for another 100,000 miles. Matt was amazed.

Part of me thought "Boy, I just scored a perfectly running and driving Jeep for free!" but the look on Matt's face when he first cranked that four-liter and heard the motor purr like it had back when he bought the car at age 17 made me realize that there was no way I could take this Jeep. I just didn't have the heart.

Matt, a college student, had just turned 20 the week prior, and had been talking Brandon and my ears off all night about his adventures with his XJ; it was clear he loved the thing (he even stripped the interior to clean it—something not even I would ever consider doing), but felt forced to sell it after spending lots of time and money fixing it, only to be disheartened by the loud engine noise.

The Jeep was the first vehicle Matt had ever wrenched on, and he had done a lot to it: he swapped the fuel tank, all of the steering components, the ABS pump, the fluids in the diffs, transfer case, transmission and engine; and a whole bunch more. He was using good quality parts, too, and he was even nice enough to offer me an enormous box full of spares for cheap.

I'm a bit too young to be saying things like this, but I guess I saw a little bit of me in Matt. I remember when I was a young college student wrenching on the side of the road, trying desperately to keep my 200,000 mile Jeep Cherokee running. It's tough, and while I never threw in the towel like Matt did, I still regularly come very close to it on some of my projects.

But I never come close to giving up on my first Jeep, because that's the one that got me into wrenching and started a whole lifestyle for me. I love that Jeep dearly, and I know that if I had ever gotten rid of it, I'd regret it until the end of time. I don't want Matt regretting selling his first Jeep, especially for something as simple as a few flex plate bolts.

So yeah, I drove eight hours to, essentially, thread in four bolts. But I have no doubt Matt will be hooked on shitty old Jeeps for the rest of his life, and that makes it all worth it. Because I'm going to need someone to call for parts.

Here are a few more shots of Matt's janky 1992 Jeep Cherokee Briarwood: