An Autonomous Deep Sea Drone Might Have Found Amelia Earhart's Wreckage After 87 Years

The $9 million underwater drone can record clear images at depths of 20,000 feet

On July 2, 1937, aviation pioneer Amelia Earhart and her navigator Fred Noonan disappeared somewhere over the Pacific Ocean. Search and rescue missions turned up no leads, and for 87 years, her disappearance has remained one of history's greatest unsolved mysteries. That is, unless an underwater drone from Deep Sea Vision is correct, and its new technology has actually discovered the wreckage, USA Today reports.

Earhart disappeared during her 1937 attempt to become the first woman to complete a circumnavigational flight of the globe. She and her navigator were last seen in Lae, New Guinea, where they had stopped to fuel their Lockheed Model 10-E Electra airplane. The two were set to stop again at Howland Island, but the plane never arrived.

Since then, everyone from academic researchers to conspiracy theorists have speculated on what happened to Earhart and Noonan, but there has been little evidence to work from. But earlier this year, an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV), or drone, very well may have found the remains of the twin-engine aircraft.

South Carolina's Deep Sea Vision, a marine robotics company, used a $9 million underwater drone called the HUGIN 6000 AUV from Kongsberg to scope out the sea floor around Howland Island. The drone uses a newly developed type of sonar called synthetic aperture sonar (SAS), which can produce high-resolution pictures of the seafloor at distances of 20,000 feet. The tech has already been used for everything from classifying underwater critters we humans struggle to see with the naked eye, to better understanding shipwreck sites.

I'm no scientist or engineer, so I'll turn it over to Scott Manley on YouTube, who has shared an in-depth but still easy to understand explanation of SAS as it's used in satellite systems:

Speaking to strategy expert Abby Rakshit, who has spent a decade in technology and operations and advising Fortune 500 companies in deep tech explained to me that this SAR technology application works a little like if you turned on flash on your iPhone telephoto lens and moved around a forest — but that that process is repeated over a larger area with a higher level of data fidelity, so you could actually seek out a specific tree whose dimensions you may already have. The radio waves can carry rich information over the simple communication channels that already send out our cell phone texts, and they can capture a wide range of data across their imaging path. What makes this discovery unique is that the discovery from Deep Sea Vision was able to match the dimensions of the Lockheed 10-E Electra, Earhart's plane, to the image; that gives this discovery more credibility than other assumed discoveries of her wreckage.

The vessel is totally autonomous; once it's launched from a ship, you don't even need a remote control connection to help HUGIN navigate. That's a huge boon for anyone who studies those hard-to-reach locations on our planet. When the AUV completes its mission, it just floats to the surface and sends out a signal to alert the launch boat to its location. Then, it can be easily collected, and the data onboard can be downloaded and analyzed.

In February, Deep Sea Vision released a blurry sonar image of what roughly resembles a plane. The image was taken at a depth of 16,400 feet (which is 4,000 feet deeper than the Titanic wreckage), within a 100 mile radius of where experts believe Earhart's plane fell into the ocean. While the initial image is extremely blurry due to a broken camera on HUGIN, investigators intend to send the repaired drone back out to the location to collect better images.

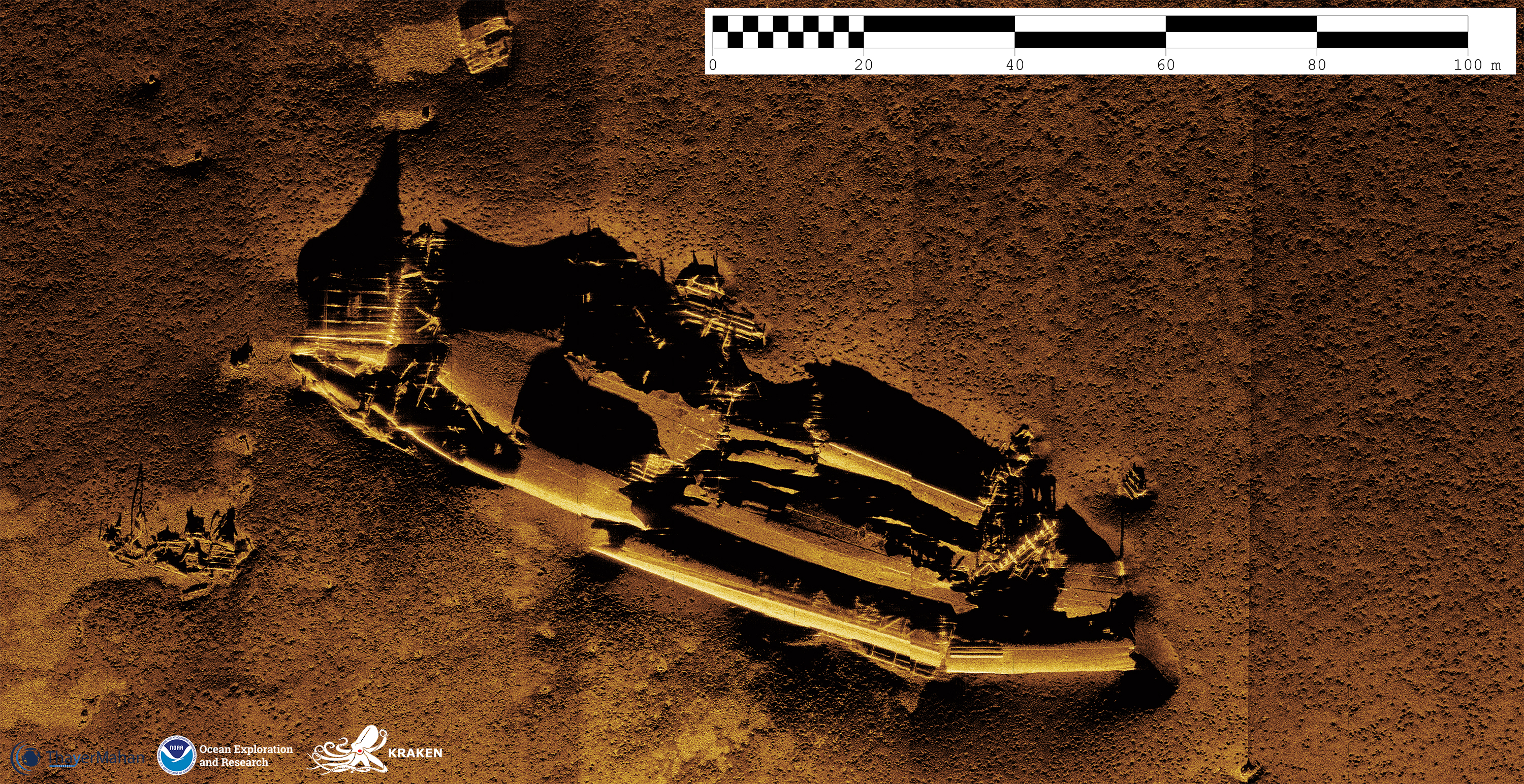

When conditions are right and the craft is in full operation, synthetic aperture sonar systems can take some exceptionally detailed photos, like this one:

Obviously, we still need more evidence to confirm whether or not this is truly Earhart's wreckage — but the very fact that this technology currently exists is the very definition of awesome. Along with its continued Earhart expedition, Deep Sea Vision hopes to also discover the remains of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, as well as those of The Royal Merchant, an English merchant ship laden with gold and silver that went missing all the way back in 1641.