Hard Driving Shows That NASCAR Still Has To Contend With Its Racist History

When Wendell Scott contested his first official NASCAR Grand National Series race in 1961, he was already 40 years old and had been racing for 26 of those years. He wasn't young, he certainly didn't have anything close to the best equipment, he was going up against some of the sport's most iconic drivers, and he did it all while carrying the baggage that accompanied the shade of his skin. And his story is a damn good reminder that NASCAR still has a lot of work to do when it comes to reckoning with its racist past.

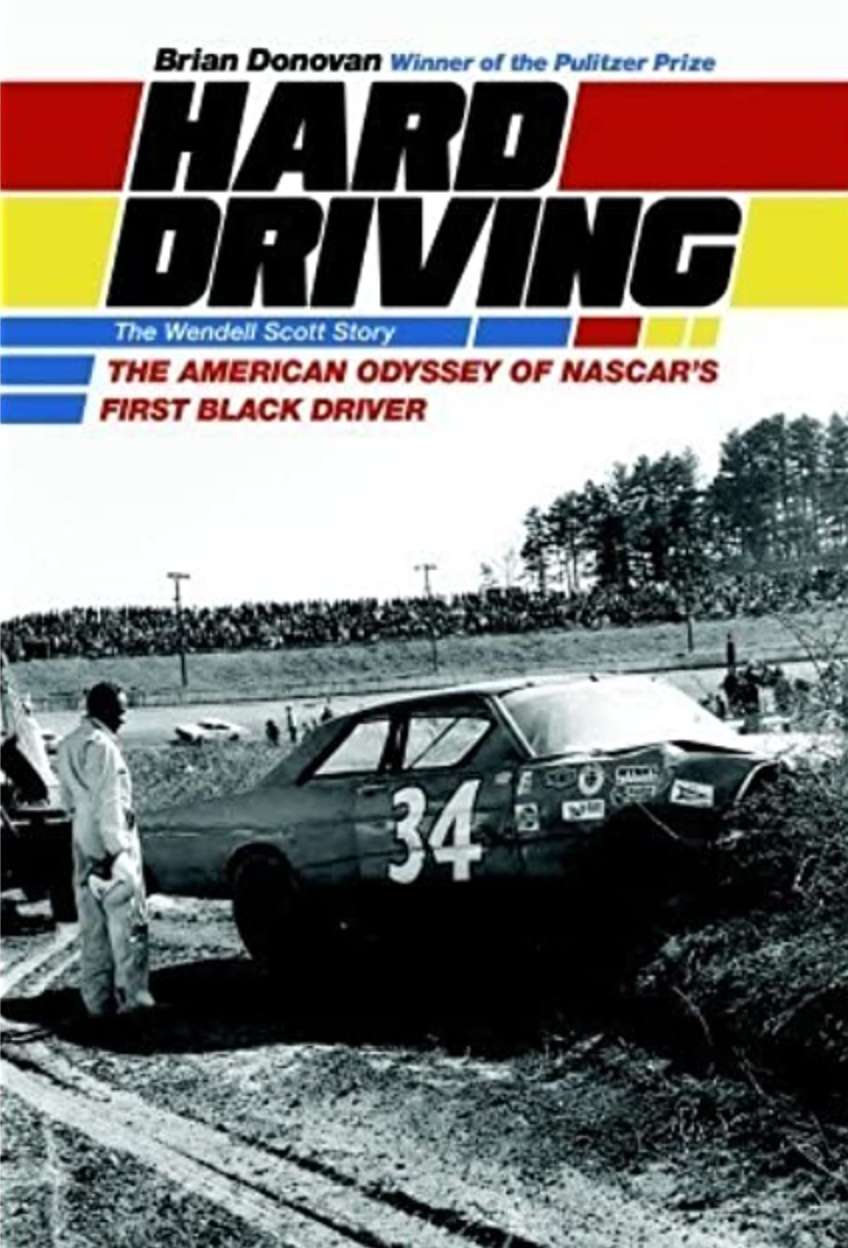

(It lives! Welcome back to the Jalopnik Race Car Book Club, where we all get together to read books about racing and you send in all your spicy hot takes. In honor of being trapped indoors, I've made the reading a little more frequent; every two weeks instead of every month. This week, we're looking at Hard Driving: The Wendell Scott Story by Brian Donovan, a biography of NASCAR's first winning Black driver.)

Scott was born in Danville, Virginia in 1921, and he knew one thing for certain: He wanted to be his own boss. Danville's economy was deeply entrenched in its cotton mills and tobacco processing plants, and Scott had much bigger dreams for himself. Even as a child, he began picking up auto mechanic skills from his father, and he started earning money to be able to afford the freedom of his own bicycle. It was with the bike that he learned to love speed, a trait he'd never rid himself of.

After a stint in the military during World War II, Wendell settled down in his hometown, began building a family, and opened his own auto repair shop. To supplement his income—and to feed what ultimately became the seven mouths of his children—Scott took to running moonshine on the side. Not long after, he decided to see what his machines could do in competition at local stock car races.

Hard Driving does a great job establishing Scott's history, but it really gets its teeth when author Brian Donovan begins talking about Scott's racing career because it's the point where we see Scott walking the very difficult line of being a Black man in a predominately white sport.

Throughout his career, Scott adopted a fairly amicable stance. He's described as always being polite and hard-working, always keeping his head down and letting his driving speak for itself. The problem was, Scott couldn't exactly race his competition the way they raced him. As a Black driver, he was often intentionally targeted during races, but Scott couldn't retaliate. He couldn't bump a driver out of the way for a win. Being deferential to his competitors was often the only way Scott would even be allowed to compete; he was supposed to be a marketing tool, not a threat.

His experiences remind me a lot of something Giovanna Amati said in the documentary Beyond Driven: "The truth is that they don't accept you. They accept you when you are way behind them. When you start to get closer, they don't even talk to you anymore. In the pit lane, drivers don't even look at you."

It was fairly similar for Scott. Many drivers didn't mind a Black man racing—they just didn't like it so much when he started specifically challenging them and contending for wins.

And it wasn't just drivers. Promoters often refused to pay Scott the money he earned due to a solid finish or the money they promised to the "hard luck" drivers that struggled during the race. Scott generally operated on a shoestring budget; being refused any of the money he was expecting often meant he couldn't afford repairs or, in some extreme cases, the gas money to get home. He and his wife remortgage their home countless times to fund his career.

Perhaps the most heart-wrenching story in the book, though, is the race at Jacksonville in 1963—a Grand National race that Scott legitimately won and was denied. A white driver, Buck Baker, was awarded the trophy at the end of the race, and it was hours after when Scott demanded the timing sheets be reexamined that the officials named him the winner. By then, everyone had left. Traditionally, the winning driver kissed the trophy girl; because she was white, Donovan hypothesizes that the promoters didn't want to cause a stir by having a black man kiss a white woman. Scott was given a poorly-carved wooden trophy at the next race.

That was an event fairly representative of Scott's entire career. While he raced, Scott often maintained that he was treated fairly when compared to his white counterparts, but it was obvious he wasn't. Scott was denied factory rides in favor of white drivers. He would drive across the country to Riverside only to be turned away at the gate. He was consistently denied entry to races held at Talladega. And while Brian France promised Scott that he would always be treated fairly—and while France's influence did admittedly help Scott at least earn the money he was promised—there were still huge disparities in Scott's treatment. It was only after Scott was injured and could no longer compete that he openly recognized the discrimination.

Donovan does a great job getting the whole story. He conducted interviews with the Scott family as well as with his competitors, both sympathetic and not. Many people denied Scott was ever treated differently because of his race. Others said that, had he been a white man, factory teams would have bent over backwards to give him a competitive ride.

There are layers to reckon with here, and Scott's treatment is only one of them. During Scott's tenure in racing, for example, Talladega Superspeedway was founded via a collaboration between France and Alabama governor George Wallace—the latter of whom campaigned on a platform of "segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever" and was notorious for standing in front of the University of Alabama to block the entrance of black students. When Wallace eventually ran for President, France helped him win the Florida primary. It's difficult to argue that Wendell Scott could be treated equally when the odds were so heavily stacked against him.

And that's not something that's gone away simply because times have changed. Brian France Jr. did, after all, endorse Donald Trump for President. Even today, the family of Black NASCAR driver Bubba Wallace has acknowledged that he's been treated differently because of the color of his skin.

Hard Driving is the kind of book that every race fan needs to read.

And that's all we have for this week's Jalopnik Race Car Book Club! Make sure you tune in again on October 4, 2020. We're going to be reading Lone Rider: The First British Woman to Motorcycle Around the World by Elspeth Beard. And don't forget to drop those hot takes (and recommendations) in the comments or at eblackstock [at] jalopnik [dot] com!