Ford's 1958 Nucleon Concept Was 'Atoms For Peace' On Wheels

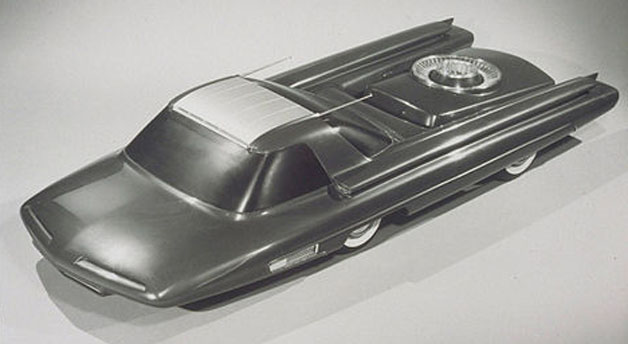

It was the late 1950s. GM's Motorama had the public mesmerized with jet-inspired fin-festooned and chrome-covered show cars. Ford needed something to match. Ultimately, they decided to go with the nuclear option. They built an "atomic-powered" concept car. They built the Ford Nucleon.

Sure, jets were fancy and fast, but this was the Nuclear Age. The immensity of atomic power was on everyone's minds and rightfully so. Ford saw an opportunity to turn that infatuation with what happens when you split an atom apart and jumped on it.

By 1958, the nuclear arms race was in full swing, with the United States and Soviet Union leading the small club of nuclear-armed states into a new era of battle, or at least steely-eyed confrontation. There was real power there. Americans had seen its impact only thirteen years prior over Japan. The question was then what might be done to turn this technological breakthrough into something creative. Something that could benefit humanity rather than tear it apart.

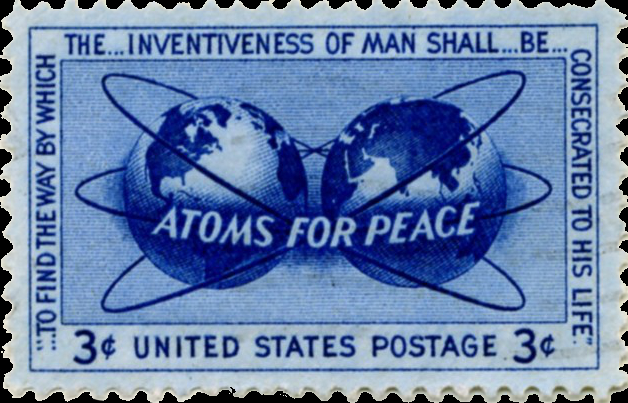

Five years before the Nucleon was shown off to the public by Ford, President Eisenhower delivered a landmark speech to the United Nations General Assembly on the issue nuclear technology and society. The speech, known as Atoms For Peace, was largely an attempt to convince the international community, and the USSR in particular, to agree to an international effort to monitor the arms race, which Eisenhower made clear had become a grave threat to humanity.

But that's not all Ike said during his speech. To soften the blow of a warning of possible nuclear annihilation, the president channeled Isaiah 2:4, proposing that, like swords beaten into plowshares, the fissile material supplied to the nascent International Atomic Energy Administration, the IAEA, by the various powers who had already reached nuclear capability. The IAEA would then use it to find peaceful industrial uses for the destructive technology. The goal was not just technological. It was political too. Eisenhower hoped that such cooperation would provide a venue of the alleviation of the mistrust between the great powers that had caused the arms race to begin with.

As for efforts to turn nuclear weaponry and the associated technology into tools for development and understanding? The program did result in a few reactors being built with American help in places like Iran (yes, really. This was back during the days of the US-aligned Shah) and India (which would form a basis on which Indian nuclear weapons would be developed in the 1970s), but the result was ultimately the proliferation of dangerous nuclear technology for strategic aims rather than the cultivation of international understanding and cooperation.

The IAEA did indeed come into existence, and it has remained the primary watchdog organization involved in nuclear non-proliferation efforts since the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty was signed in 1968, including in North Korea and Iran.

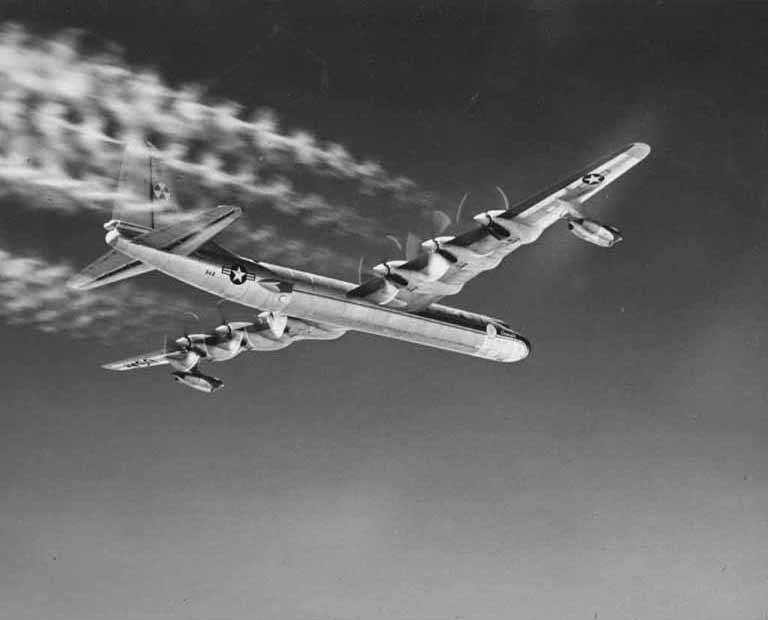

Alternative uses of nuclear technology did come into existence in the wake of the speech though, but they were largely programs undertaken by the government or by corporations without international cooperation, including Convair's NB-36H nuclear testbed airplane and our Ford Nucleon.

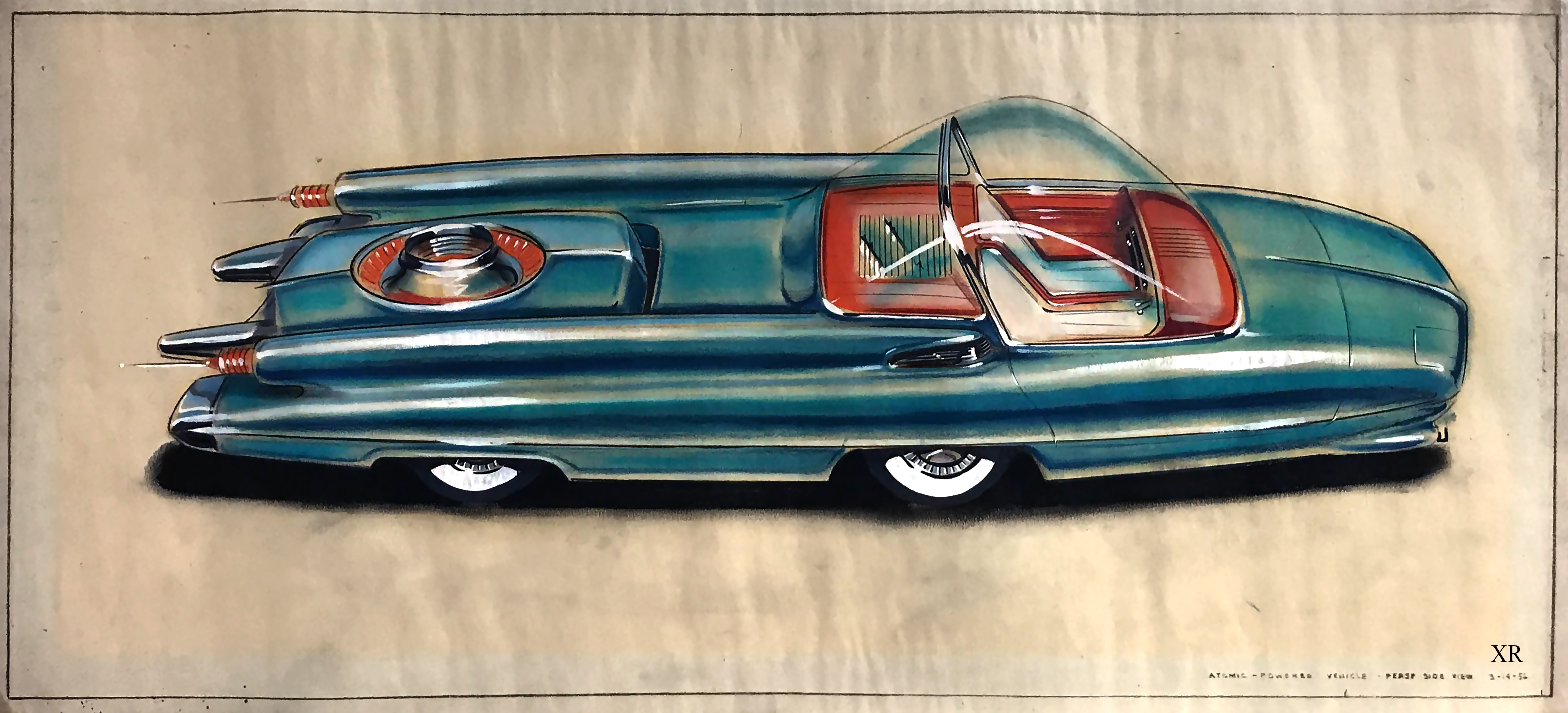

Ford's vision with the Nucleon was essentially to take the premise behind nuclear propulsion as used in submarines and aircraft carriers and adapt it for road use. The benefits of nuclear powered road vehicles seemed clear at the time. Ending the need for regular fuel stops could be enough, but the prospect of driving the car of the future might have even been more appealing.

Like in an early nuclear submarine, the nuclear reactor would power two steam turbines. One would drive the wheels directly the second would drive an electric generator to power the lights, climate control and other features.

Interestingly, Ford's engineers designed the powertrain to be modular. A number of replaceable power-packs were envisioned, including a performance model and an economical version with taller gearing. The power-packs were predicted to provide 5,000 miles of range, which is not enough to last the lifespan of a car but certainly is more time between fill-ups than any internal-combustion or battery-electric car can manage these days by orders of magnitude.

Now, despite President Ike's assurances that nuclear technology could foster a new era of peace and international understanding, there was still the issue of dangerous radiation. Ford was prepared for that, though. To keep the occupants of the Nucleon safe from the radiation propelling their vehicle, the cabin was pushed far forward, with the driver sitting ahead of the front axle, kind of like a UAZ Buhanka or the Ford Econoline which launched not long after the Nucleon hit the car show circuit.

This actually served a second purpose as well. Nuclear reactors are heavy, and the lead shielding necessary to keep the occupants inside alive is pretty bulky as well. With the load of the powertrain straining the rear axle, the front axle needed to pick up the slack.

The cab-forward shape of the Nucleon was only one component of its atomic-age styling. The car's large windshield and chromed reactor housing were a real match for what GM was showing at their yearly Motoramas. Versions of the car were shown both with tall fins out back and without. I think that the car's shape is balanced out by the twin tails. Without them, the car looks to me like it should have a pickup bed.

As you probably guessed, the Nucleon never made it past the concept stage. Ultimately, the fear of nuclear holocaust outweighed the hope for a nuclear-powered future. Windscale, the first commercial nuclear accident, had occurred just a a few months before the Nucleon would be revealed, and the possibility of a fender-bender releasing even a little bit of the destructive force that had ended World War II proved to be too large a risk. The Nucleon was shuttered away, another doomed concept car without follow-through.

The Nucleon never made it, but that didn't stop the United States from continuing to explore other uses for nuclear technology beyond power generation and war. Also beginning in 1958 and nodding even more directly at Isaiah's prophecy for repurposed armaments, Project Plowshare sought to find heavy engineering uses for nuclear explosions. Over 27 different tests, the program attempted to find ways to use nuclear armaments for earth-moving and mining. Ultimately, the government decided the program was no match for conventional approaches.

Ford made the same decision and we never saw a production version of the Nucleon. The project may seem wild in retrospect, but manufacturers did learn a thing or two from the doomed atomic automobile: Both Better Place, a now-closed Israeli electric car start-up, and Tesla have both shown off battery-switching technology that is similar to the reactor-replacement scheme envisioned by Ford for the Nucleon. Neither of those projects made it either, but they do demonstrate how the project's ingenuity was not totally cut down by the glaring safety issues that ultimately were its demise.