Falling Space Junk Is A Growing Problem That Is Only Going To Get Worse

In the rush to fill space with more and more satellites, have NASA and SpaceX overlooked properly assessing the risks of space junk falling back to Earth?

Earlier this year, the peace of a Florida neighborhood was shattered when a chunk of junk from the International Space Station crashed through a home. This was followed in May by a 90-pound piece of a SpaceX Dragon ship that crashed into a camping resort in North Carolina, begging the question: Are space agencies doing enough to protect us from falling space debris?

The answer, it turns out, is probably not. As government agencies such as NASA and private companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin race to send more and more tech into orbit, a new report from Ars Technica warns that more must be done to understand space junk.

The space above our planet is currently filled with everything from remnants of the Apollo program to waste from the ISS and even defunct satellites. To remove this junk, scientists usually spend years working out safe ways to bring things like out-of-service satellites back to Earth, which involves forcing them to burn up in our atmosphere or crashing back into the ocean. That doesn't always go to plan, however.

In fact, this year has seen a bizarre spike in the number of chunks of space junk landing on American soil. The spike comes as an influx of new satellites are being launched as part of the Skylink system and private companies begin sending more and more people into the cosmos.

This all means that the safety of innocent people back on Terra Firma is at risk as falling space junk becomes less predictable. According to Ars Technica, experts have warned that there are now too many variables at play when it comes too predicting how space junk will now fall back to Earth.

As a result, the risks of space junk crashing back onto land is rising. In the case of a fragment of a Dragon ship that crashed onto U.S. soil, everything from the weave of the materials used to the way it fell through the atmosphere influenced how the craft survived the trip, as Ars Technica explains:

The orientation of a spacecraft as it falls into the atmosphere may also factor into survivability, Greg Henning, manager of the debris and disposal section within Aerospace's space situational awareness department said.

"Is it tumbling? Is it reentering in a stable configuration? There are so many things that go into what actually happens during a reentry," he told Ars. "It just makes it that much more complex to figure out if something is going to survive or not."

While tests can be done before a defunct space craft begins its descent, those calculations don't always offer the best insight. In fact, NASA and SpaceX engineers projected the Dragon parts that fell to Earth would be burned up in the intense re-entry process, with no part of it expected to survive.

That didn't happen, though, and remnants touched down on American soil. Now, NASA and SpaceX will analyse the remains to give them a better idea of how components and materials behave when free-falling from space. As Ars Technica adds:

"During its initial design, the Dragon spacecraft trunk was evaluated for reentry breakup and was predicted to burn up fully," NASA said in a statement. "The information from the debris recovery provides an opportunity for teams to improve debris modeling. NASA and SpaceX will continue exploring additional solutions as we learn from the discovered debris."

So far, the close encounters we've had with falling space debris haven't harmed anyone in America. And while the European Space Agency asserts that the annual risk of an individual getting injured by falling debris from space is "less than 1 in 100 billion," that risk could rise.

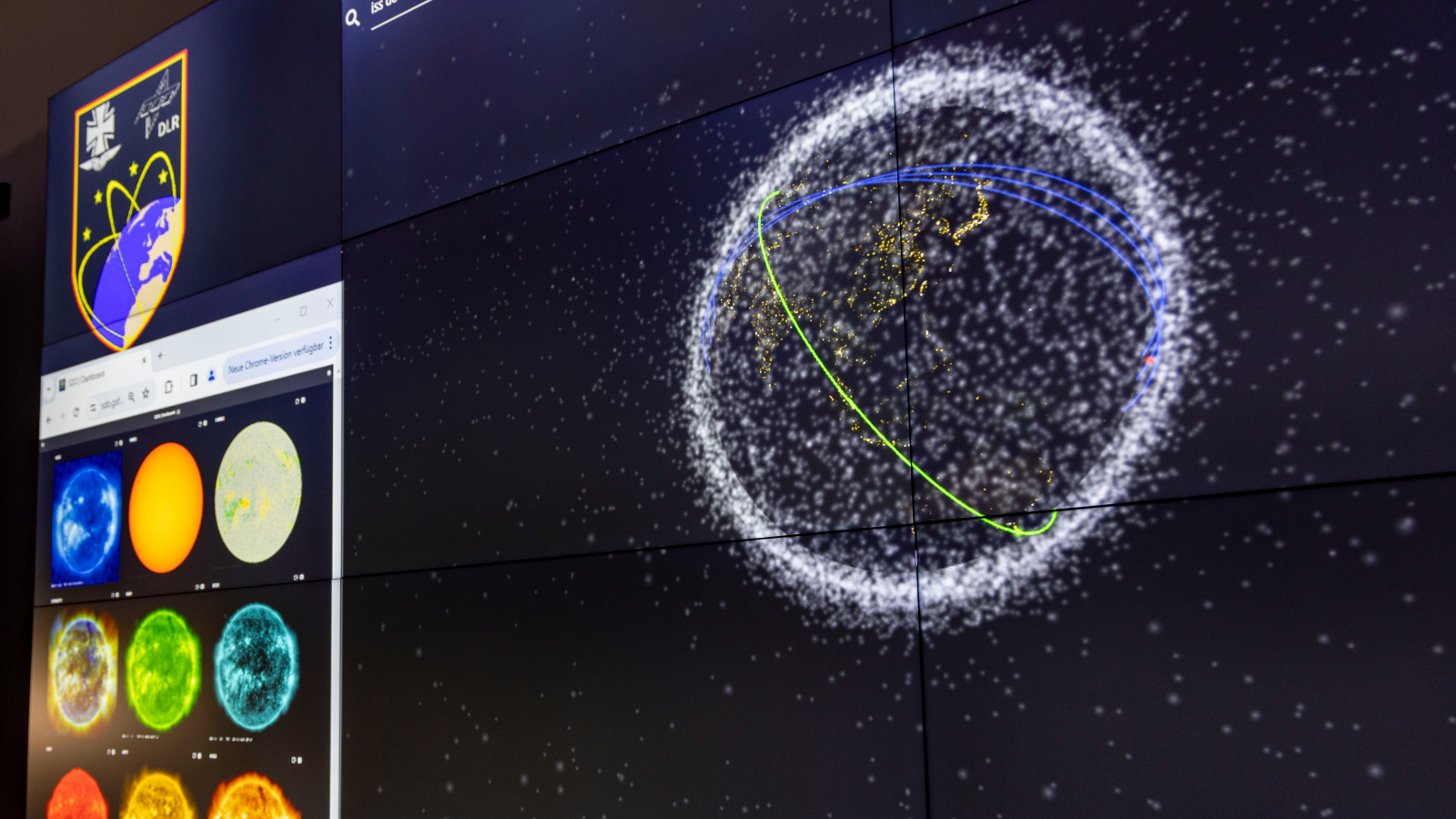

There are now more than 120 million pieces of debris floating in space right now, and while many will certainly never make land, the risks they pose will only continue to grow as that number rises.