EV Credits Mostly Go Towards Rich People Who Would Buy EVs Anyway: Study

Most beneficiaries of the federal government's electric vehicle tax credit would have bought an electric vehicle anyways even if they didn't receive a subsidy, according to a new working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research.

The study, conducted by researchers from Peking University, Cornell University, and the environmental non-profit Resources for the Future, further suggests nearly all new EVs are replacing some of the most fuel-efficient vehicles on the road to begin with.

From the study:

Our results suggest that vehicles that EVs replace are relatively fuel-efficient: EVs replace gasoline vehicles with an average fuel economy of 4.2 mpg above the fleet-wide average and 12 percent of them replace hybrid vehicles. Federal income tax credits resulted in a 29 percent increase in EV sales, but 70 percent of the credits were obtained by households that would have bought an EV without the credits.

And, for the 109,449 EVs purchased in 2014:

Among gasoline vehicles replaced by EVs, 74 percent of them have fuel economy above 25 mpg. The vehicle models that were replaced by EVs most are: Honda Accord, Toyota Prius, Toyota Camry, Honda Civic, Toyota Corolla, Nissan Altima, and Chevrolet Cruze. This substitution pattern suggests that EVs mainly attracted consumers who were originally choosing mid-size and fuel-efficient gasoline or hybrid vehicles, rather than gas-guzzlers such as large SUVs or trucks.

This is critical, the researchers note, because assuming EV buyers are replacing vehicles with average fuel economy would overstate the environmental benefits EVs have had by 27 percent.

It's important to note that these findings are not from the researchers directly comparing vehicle ownership records for those 109,449 drivers. Instead, they looked at a large consumer survey, the U.S. New Vehicle Customer Study by MaritzCX Research, for four years that included a whole bunch of questions including what cars people bought, what other cars they considered buying, and their income. Then they combined that data with other large macro sets like vehicle sales figures, built a mathematical model, and estimated these effects.

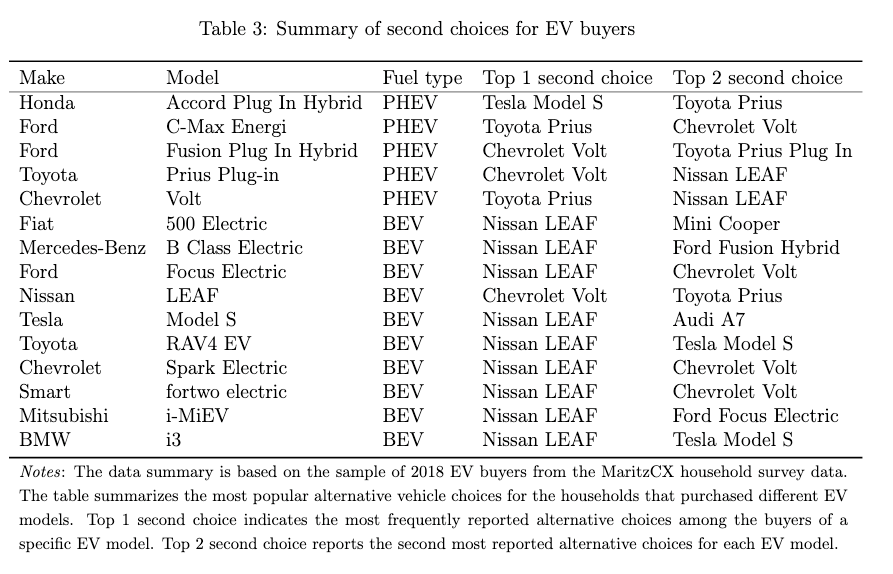

That being said, some of the insights don't require any advanced modeling. For example, a quick glance at a table showing the second-choice vehicle of EV buyers demonstrates that they're pretty much all in the alternative fuels market and they're mostly willing to spend a lot of money on a car (the Leaf appears to be virtually everyone's second choice).

Still, the broader conclusions the paper reaches with their model aren't too out there: in 2014, EVs were generally much more expensive than the median car, so the maximum $7,500 tax credit didn't balance out the price difference. It makes sense EV buyers would value EVs for reasons that go beyond pure cost comparisons.

Nevertheless, from a public policy standpoint, this raises important questions about the tax credit. Why pay rich people to buy a car they're already going to buy, or to buy a slightly more efficient car than the one they might have otherwise bought?

For one thing, this is simply how new technology tends to work: it's expensive at first, rich enthusiasts are the only ones who can afford it, but that spurs further cost-cutting innovation and mass production, until eventually it reaches a price the masses can afford. Taking the researchers' model at face value, that still means about one in three EV buyers during a critical growth phase were spurred to buy EVs at least in part due to the federal tax credit.

Indeed, the researchers don't use these conclusions to argue against government tax credits for EVs, especially now that the industry has matured some. Instead, they argue the findings suggest the efforts need to target price-sensitive consumers—especially those with lower incomes who may want an EV but can't afford one—or those driving fuel-inefficient vehicles where the environmental benefits would be greatest. California's Clean Vehicle Rebate Project already takes household income into account, but there's currently nothing in the country that additionally incentivizes replacing gas-guzzlers. Maybe there should be.