How The World Ran Out Of Tour Buses

When pandemic restrictions ended, every band on Earth wanted to get back out on tour. But lasting COVID-19 disruptions meant many couldn’t find a bus or RV.

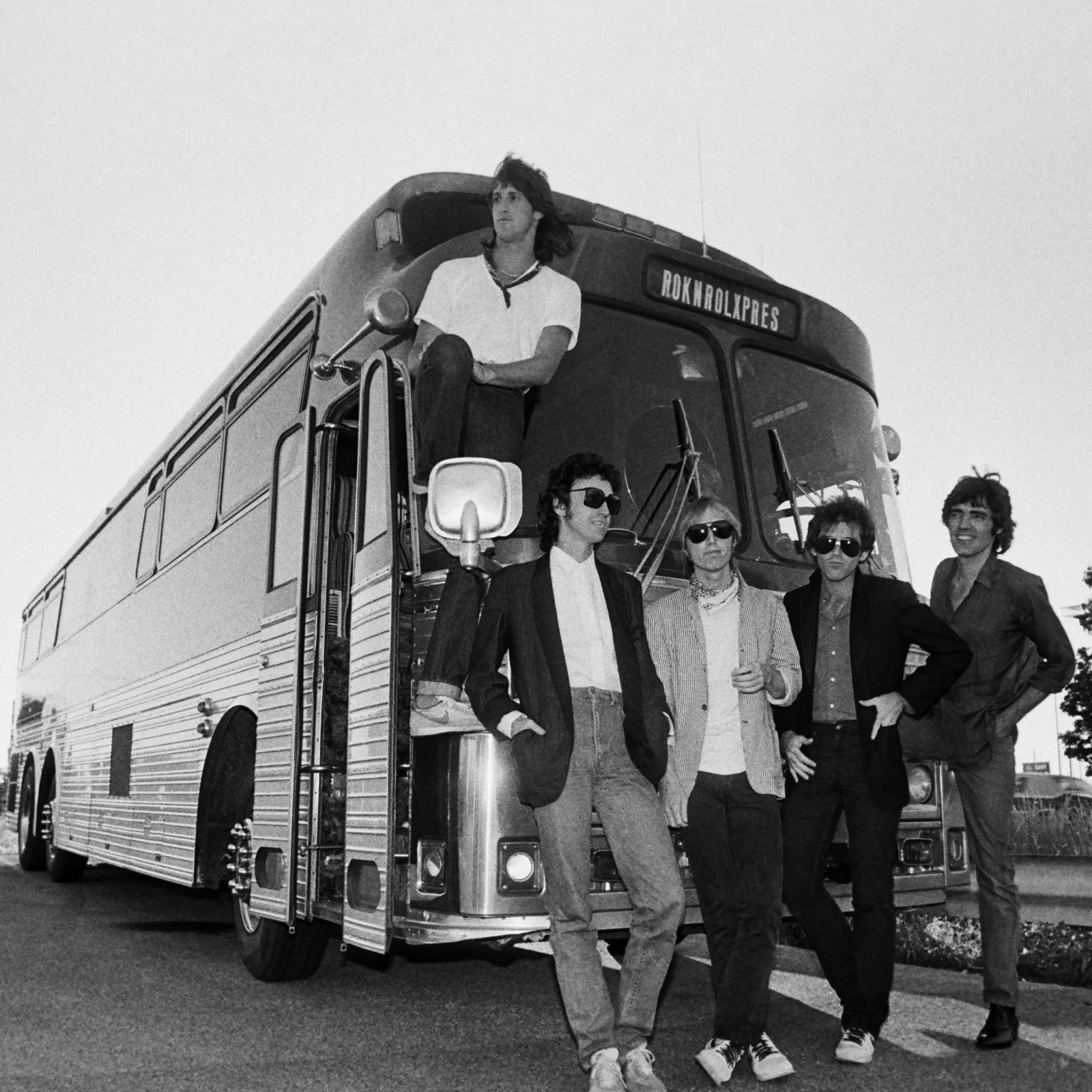

If you've ever gone to a major concert, there's a good chance you've seen the monolithic tour buses parked up near the venue. These blacked-out behemoths embody the mystery of life on the road for a rock band, and evoke questions about what their tinted windows might hide.

Buses like this are packed with the creature comforts any self-respecting musician needs for a life on the road, beginning with a fridge full of beer, beds and bathrooms and going on from there to include everything from massive TVs to cigar humidors and even mobile recording studios. Here in America, they're also usually slathered with chrome accents adding to the cool aesthetic of a rock-star lifestyle.

Just a few years ago, it was pretty easy for bands to get hold of buses like this to take out on the road. The first way to do this, if you're a big name, is to buy one for yourself and keep it running on tour after tour. If you're a megastar like Dolly Parton, you can even rent it out for fans to stay in.

But for musicians that haven't written something on the level of "Nine to Five," the best way to track down a tour bus is to rent one.

"Before the pandemic, there seemed to be more buses available," says Jamie Morral, president of Pennsylvania-based rental firm JGM Coaches. "Bands would be able to book their tours and feel confident that they would find a bus,"

For almost two decades, Morral and his firm loaned out buses to bands like Killswitch Engage, Hot Tuna and Simple Plan for their American tours. But on March 15, 2020, states began implementing lockdown orders as COVID-19 spread across the country.

"The whole industry was paused for two years," says Scott Bell, tour manager for American rock band The Menzingers. "So now, everybody has come out to make money and everyone has to tour."

Fierce Competition

Now, almost three years later, bands, musicians and artists of all kinds are itching to get back out on the road and make up for lost time with fans. Because of this, competition for everything needed to put on a psychedelic show is fierce. Venues, equipment and tour buses are all in high demand as everyone from Taylor Swift to Def Leppard tries to hit the road now that they're free to travel the world once again. Rabid competition is leading to sky-high prices, canceled reservations and soaring demand for all manner of equipment, particularly tour buses.

"You had the likes of Diana Ross on waiting lists with bus companies hoping bands would cancel a tour so they could get a bus," says Graham Forster, a tour bus driver for Irish company Crosslink.

So, how the heck did we get here?

First up, the music industry changed. With the advent of streaming, album sales and new music releases aren't enough to make being a recording artist a full-time job for many. Spotify pays out just $0.004 per stream, so revenue for bands and singers has increasingly come from merchandise and ticket sales.

So when the pandemic put large events and concerts on hold, many musicians struggled. Now that restrictions have been lifted, "Everybody is trying to put money in their checking accounts," says Morral.

No More Buses

But the pandemic took more than just money from artists' purses. With the industry on hold, bus companies struggled as work dried up. While some firms were able to stay solvent by, for instance, loaning out their buses to healthcare providers to act as mobile vaccine hubs in the pandemic, this was either done at a loss or didn't bring in the kind of revenue they were used to. Some had to make the difficult decision to sell vehicles or even close up shop for good.

"Some of those companies that went bankrupt during the pandemic, not all those buses have been bought up or are being run by other companies yet," says Morral. This means there's now a shortage of buses as these vehicles are still waiting to be snapped up by other operators. "If you take 20, 30 or 40 buses out of the entertainer equation then that's a lot of buses."

For this reason, the price of tour buses is skyrocketing. Where bands could usually expect to spend 20 to 35 percent of their budget on the bus, according to Morral, that's no longer the case.

"I've had managers and artists write to me since this all started telling me they would pay double if I could give them buses," says Morral. "I've heard stories of people having their buses pulled and given to someone else. It's bad business."

That's a story echoed by Bell of Scranton, PA punk band The Menzingers, who told us of a metal band that was forced to pull its European tour after the bus company told them to wire them thousands more dollars, as another artist was trying to outbid them.

Driver Demand

All this chaos isn't simply around securing the bus. It's also about securing the driver for your bus. Morral has stories about rental companies across the country that have "20 to 30 buses just sitting on their lot because they can't find drivers for them."

"It's definitely a drivers' market now," says Forster, a UK-based tour bus driver who's driven for the likes of Annie Lennox, Slipknot, Metallica and Robbie Williams. "I heard of drivers asking for £400 (roughly $480) a day and they were getting it. Because the companies wanted the buses out and working."

That's roughly three times the normal rate for a driver in the UK; Forster says he's usually paid £130 (around $156) for every day that he's out on the road. But with so much money to be made, why aren't more drivers heading out on tour?

"I think a lot of it is people got comfortable being home," says Morral. "In our industry the driver is going to be gone 300 plus days a year. Then they got home and some of them, especially those who are married, got a job where they're maybe driving trucks and they're home every night. They got used to that."

Some veterans of the industry are, understandably, now reluctant to return to a life on the road. That life saw Forster spend just 14 days at home in 2022 as he covered thousands of miles driving artists like American rapper Gashi across Europe. Despite this, he says he never considered switching lanes when the going got tough.

"During the first three months of the lockdowns it was like a vacation," Forster says. "Then I became bored. I volunteered as a swab taker at drive-in test centers, then when that finished I went onto trucks for a while. That basically reminded me why I didn't like doing trucks."

As soon as touring got underway in the UK again, Forster was back out on the road. When he was reunited with his Setra 431 bus, he found himself returning to an industry that had seen many drivers leave and few new ones step in to take their places. Those that had joined were struggling to adapt to their new rides.

"Drivers are being taken on directly from service buses and tourist buses and into rock and roll. But they are a different animal altogether." Driving a musician's tour bus, he says, requires a gentle approach as the buses are much larger. On top of that, you're often driving sleeping passengers around, so you can't risk jolting your star out of bed by taking a corner too quickly or slamming on the brakes at a red light.

Now, even for drivers who have stepped away from a life on the road, the calls keep coming for them to settle back into the driver's seat.

"We met our current guitar tech through driving vans," Bell says. "He had always been a good guitar player, so we were like, 'hey Kyle, you want to be our guitar tech?' Now, he gets called all the time asking if he'll come back and drive for three days out in Canada."

Is There a Fix?

This shortage of drivers means that, at present, it doesn't make sense for companies like JGM to snap up out-of-service buses or place orders for new units.

"I don't make dumb business decisions like going out to buy ten brand-new buses just because the market is hot right now," says JGM's Morral. "I think the market is going to go back to what it was, and I think there will be buses readily available again."

But what will it take for the industry to get back to how things were pre-Covid? The answer seems to be time; time to train new bus drivers, time for artists to end their tours and time for the appetite for live shows to return to normal. But Forster warns things may get worse before they start to improve.

"A lot of the old school drivers, like myself, over the next two years will be retiring," he explains. "Then there will be a bigger shortage of drivers and I reckon it'll take easily five to 10 years."

So if you're considering a career change, this might be a good time for a life on the road with a rock and roll band.