Bessie Coleman Wrote History A Century Ago Refusing To Let Racism Win

The first Black and Native American woman pilot is an inspiration for all now and forever. This is why.

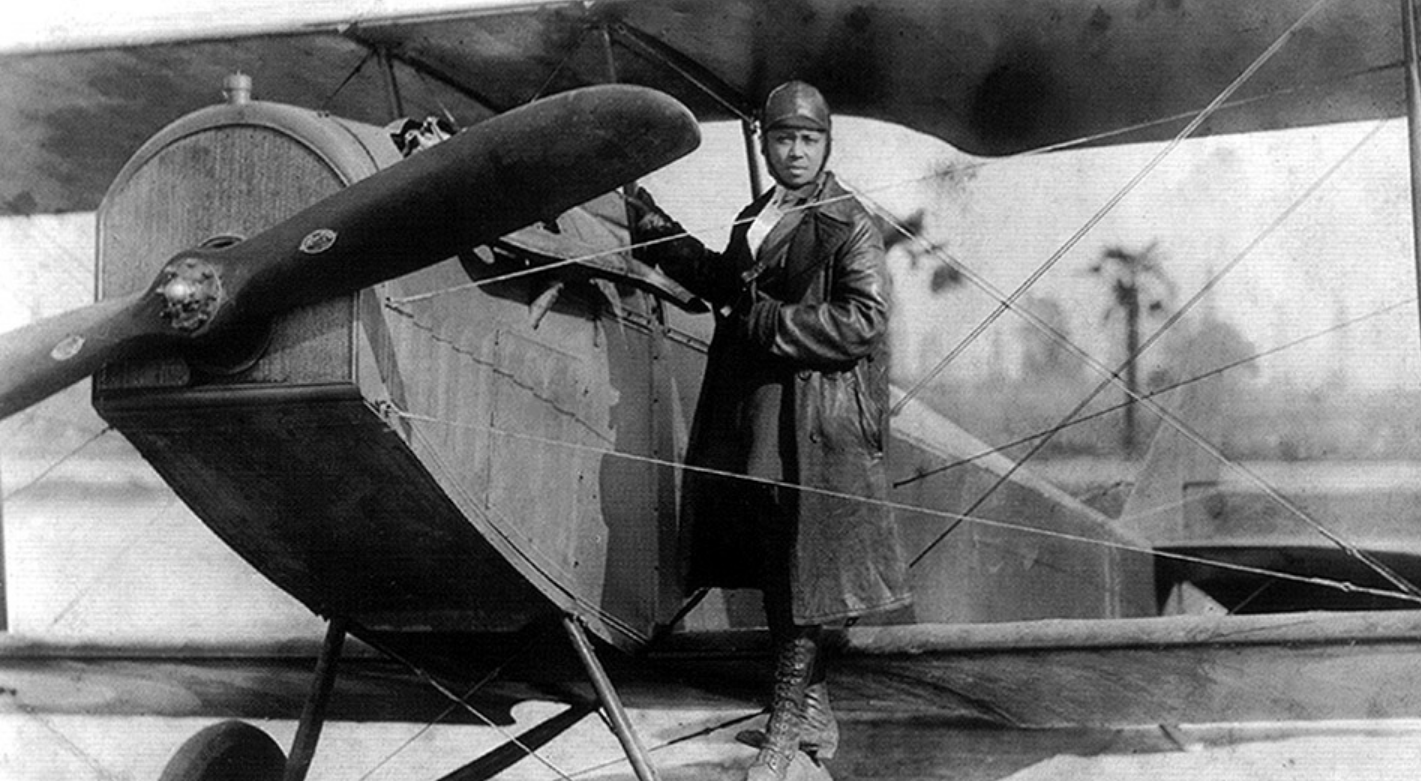

Bessie Coleman is often remembered for a quote about never taking no for an answer. But there is more to the first Black and Native American woman to earn a pilot license, overcoming seemingly insurmountable challenges along the way. She left her home and country behind to pursue her dreams, and when she returned she died flying to open the skies to Black people.

"Every no takes me closer to a yes."

Bessie Coleman was born on January 26, 1893 (many sources say 1892) in Atlanta, Texas and even from an early age, every step of her life was towards her dreams. She was born to Susan and George Coleman into a sizable family with 12 siblings. Her father, George, had Cherokee grandparents. When she was still just a toddler the Coleman family moved to Waxahachie, about 30 miles south of Dallas. There, the family worked by picking cotton and washing clothes.

In 1900, Coleman's father left Texas for Oklahoma, an area that the Official Website of Bessie Coleman notes was known as "Indian Territory" at the time. That only serves as a sad example of how bad it was to be a person of color back then. Racism of white people against Black people was rampant all over the country those days and as the site — maintained by the Coleman family — notes, Texas was even more unwelcoming to Native Americans than it was to Black people.

Coleman stayed behind with her mother and her siblings, continuing to work in the field and cleaning clothes. Later in life, Coleman reflected on this time, stating that flying was the way to a better life. From Wings Over Kansas:

"I was black, I was female, and I wanted to fly. We used to pick cotton in Texas, and I'd look up and think, If we're going to better ourselves, we've got to get above these cotton fields."

One of Coleman's first inspirations was the first sustained powered flight. In 1903, the Wright Brothers lifted from the ground in powered flight at Kitty Hawk. People have long dreamt of flying, and now the brothers proved it to be possible in North Carolina. Sadly, even as aviators made their marks on history, none of them were Black women.

The Coleman children took advantage of a traveling library that their mother took them to. There, Coleman found further inspiration in reading books about aviation. As the Official Website of Bessie Coleman notes, Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was also an inspiration. Even back then she tried to learn to fly. As HistoryNet notes, the books she wanted to pick up were about piloting:

"I read everything I could get my hands on about aviating," she later recalled. "Some of the libraries wouldn't let black girls who picked cotton borrow books, but the books I wanted were about piloting, and folks were so surprised they let me have them anyway."

Coleman's education soon expanded far past a traveling library. She didn't just graduate high school, but she used her earnings from work to attend what is now known as Langston University.

Driven From The South, Dared To Fly

She was able to attend just a single semester before dropping out. It was 1915, and she joined the Great Migration alongside the millions of Black people escaping hateful Jim Crow laws and suppressed Black vote. She ended up living with her older brother in Chicago. Another pioneering Black aviator reached the city just a year earlier, Lucean Arthur Headen.

Coleman made the best of her time there. She went to the Burnham School of Beauty Culture then got a job as a manicurist at 23. The Official Website of Bessie Coleman notes that she worked at the White Sox Barber Shop, then owned by the Chicago American League baseball club's trainer. She was so exceptional at the job that she won a 1916 contest that saw her named Black Chicago's best manicurist. But she still dreamed of taking to the skies like the Wrights did over a decade earlier.

"I was black, I was female, and I wanted to fly. We used to pick cotton in Texas, and I'd look up and think, If we're going to better ourselves, we've got to get above these cotton fields."

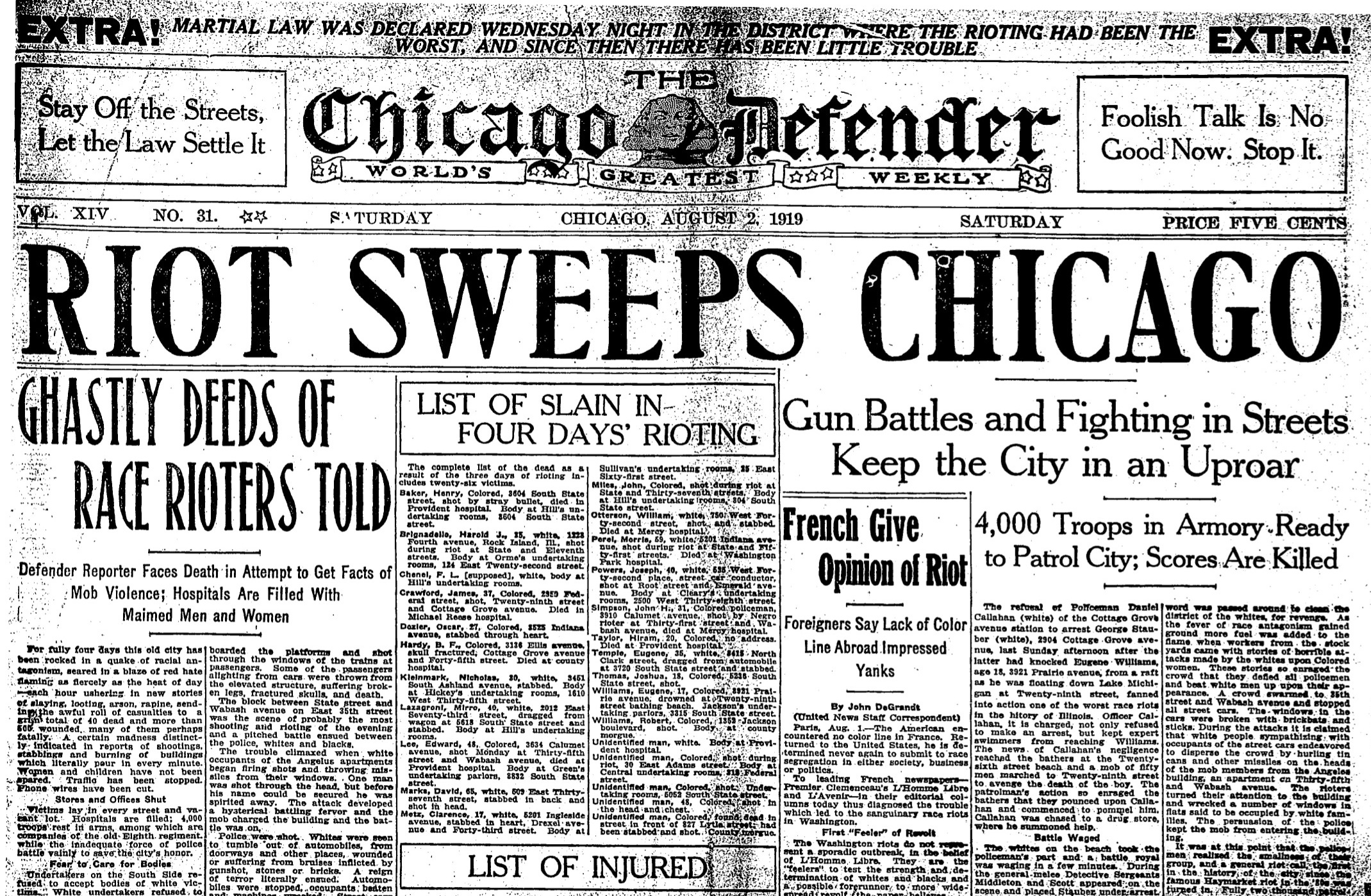

In another similarity with Lucean Headen, Coleman was a reader of the Chicago Defender, a Black-owned newspaper published by Robert Abbott. Abbott was Headen's friend and Coleman's hero. Unfortunately, like Headen, Coleman wasn't able to escape hate in her move north. For context of just how bad it was back then, both would go on to survive one of the worst race riots in American history. And that was supposed to be better than the south.

In 1919, a Black boy on a raft in Lake Michigan was stoned by white people before he fell off of the craft and drowned. Chicago erupted into a war where white people massacred Black people for four days until the National Guard returned order. In the end, 38 people died, 537 were injured and over 1,000 were left homeless, most Black.

At the same time, her brothers were overseas fighting World War 1. Coleman read about ace pilots in the war and began considering going to flight school. But it wasn't until her brother John teased that Black women can't fly that she decided to prove him and everyone else wrong, from Bessie Coleman's biography:

You [N-word] women ain't never goin' to fly, not like those women I saw in France – she smiled at him and said; That's it – You just called it for me.

Coleman applied to all sorts of American flying schools. Like Lucean Headen before her, she found that hate tried to block her advancement and dreams. Harriet Quimby — a white woman — made history being the first American woman pilot with a license from an American school. Even black male pilots like Emory C. Malick were able to score licenses from American schools. Yet Coleman wasn't welcomed and she was denied entry into every American school that she applied to. The flight schools made it clear that the vast expanse of American sky was not for Black people or women.

But Coleman wasn't willing to take no for an answer from anyone.

If America Wouldn’t Let Her Fly, She’d Go Where She Could

Thankfully, Europe was different. French women have been flying since 1889 in balloons and in 1909, the Baroness Raymonde de la Roche became the first woman pilot. Her hero and publisher of the Chicago Defender Robert Abbott found that the French were far more welcoming to anyone with a desire to fly, and Coleman set her sights on taking to the skies in Europe. She learned French, then used her earnings to set sail for France.

Coleman convinced French plane designers Gaston and Rene' Caudron to teach her at their L' École de pilotage Caudron au Crotoy. The Smithsonian Magazine notes that this is where her famous quote about not letting anything stop her comes from:

"Every no takes me closer to a yes."

Flight school wasn't easy. Coleman walked nine miles to school every day for 10 months where she learned tail spins, banking and even loops. Flying was exceptionally dangerous in those days; a simple mistake could easily lead to your death. That's not even considering that the planes themselves often failed, leading to the same result. The Official Website of Bessie Coleman notes that she saw fellow students die, but her determination was far greater than any fear of death.

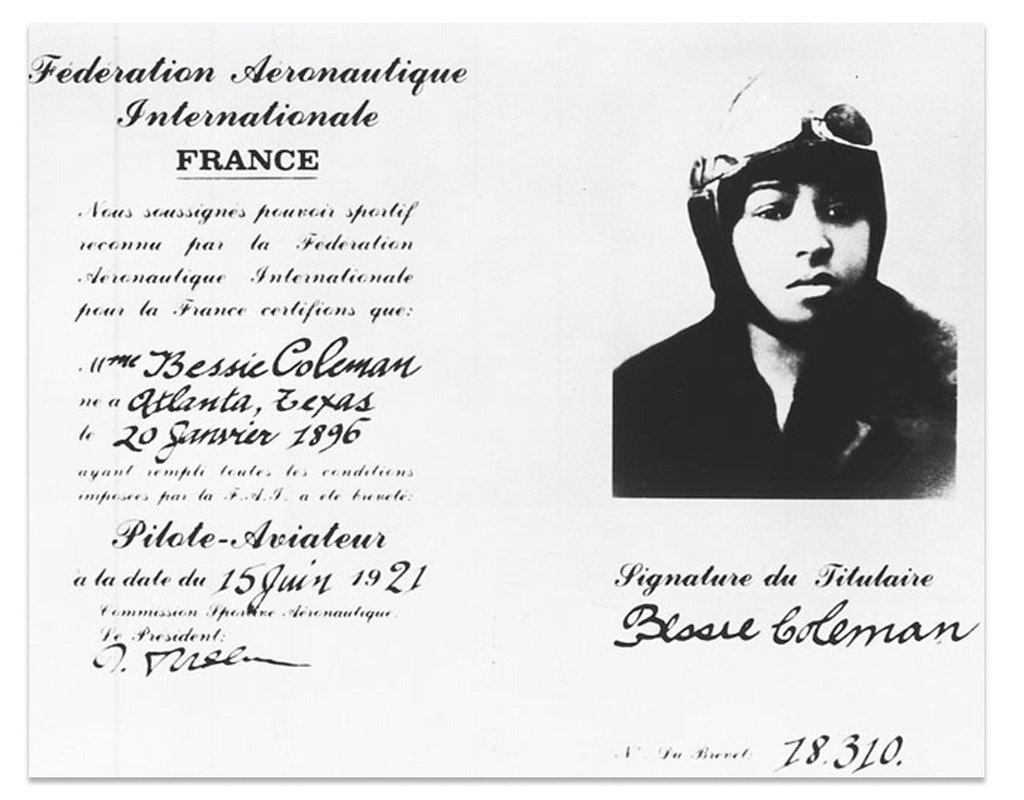

After intense training in reportedly delicate aircraft, Coleman earned her license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale on June 15, 1921.

Back at home just two weeks earlier, another deadly massacre took the lives of dozens of Black people in Tulsa, Oklahoma after white people attacked and burned the wealthy Black Greenwood neighborhood. To this day it's not known exactly how many died in the ensuing riot, with some estimations as high as 300. And to this day there is debate about whether the planes flown overhead dropped bombs into the community.

When Coleman returned to America later that year she was greeted by Black reporters from papers all over the country. She was largely ignored by white-owned papers. Aerial Age Weekly wrote:

"Miss Bessie Coleman," it said, "a colored girl of Chicago, twenty-four years old, who had been studying aviation in France for ten months, arrived in New York recently on the American liner Manchuria. She brought her credentials from the French certifying that she had qualified as an aviatrix. Miss Coleman, who is having a special Nieuport scout plane built for her in France, said yesterday that she intended to make flights in this country as an inspiration for people of her race to take up aviation."

Unfortunately, the media attention didn't mean she found work in aviation, as America still wasn't ready for Black pilots. She soon found herself sailing back to Europe to train with a WWI flying ace and to test aircraft for none other than Anthony Fokker. Fokker is known for innovative aircraft designs, including the synchronization gear, a part that allowed fighter aircraft to fire through the propeller without peppering it with bullets. His aircraft manufacturing company built everything from bombers to regional airliners until its 1996 bankruptcy.

Returning Home, Combatting Racism

She returned to the States in 1922 after having learned aerobatic stunts and earning credentials from the Aero Club of France. She earned some fame in Europe and this time, American news took notice. Now she was getting attention from the likes of the Chicago Tribune and the New York Times. A biographical essay from 2003 noted what the New York Times noted Coleman as designated by "leading French and Dutch aviators as one of the best flyers they had seen."

Bessie used her flying skills to barnstorm the country, performing dazzling stunts at shows everywhere. She took what she learned in Europe to perform rolls, loops, spins and even wing walking; all to the amazement of crowds.

It didn't take her long to become a hero for many. Here was this Black and Native American woman doing what white people said couldn't be done. Here she was overcoming virulent hate at 3,000 feet.

As the Smithsonian Magazine notes, she wasn't just an inspiration but an activist, too. America was still segregated at this time, even at airshows. Coleman refused to fly unless everyone attending got equal access. Nobody was to enter through separate gates if she were to fly. She wasn't just doing shows for the fun of it; Coleman had a grand plan to open a flight school just for Black people so that racism and sexism would no longer be a barrier for aviators.

In 1923, she was finally able to afford her own aircraft, a Curtiss JN-4 "Jenny". But her aircraft ownership would be short. The military surplus Jenny stalled at 300 feet and crashed, resulting in a broken leg and broken ribs. But just like when she saw her fellow students dying in flight school, she could only look forward to the future.

Blacks should not have to experience the difficulties I have faced," Coleman said. "So I decided to open a flying school and teach other Black women to fly. For accidents may happen and there would be someone to take my place."

Without a plane, job or money, the dream had to be put on hold. Coleman moved back to Chicago and began living a quiet life outside of aviation. But the sky beckoned, and it was just a few months before she scheduled another airshow and got back to trying to make that flight school a reality. Her skills and the massive crowds she gathered only cemented her fame and she even received recognition from politicians like the Mayor of the City of Columbus and the Governor of Ohio.

Coleman would later move her airshows south to Houston, Texas and her first southern show was on June 19, 1925 or Juneteenth. She would even return back to Waxahachie to wow crowds and to further her mission of teaching Black people to fly. She also worked hard to unravel the Uncle Tom stereotype; in an interview she stated that she wanted "to make Uncle Tom's Cabin into a flying hangar."

The Plane That Killed Her

Coleman's mission would be cut short on April 30, 1926. She was invited to do a performance at the annual celebration of the Negro Welfare League in Jacksonville, Florida, HistoryNet notes. With a donation from a white fan, she made the last payment on another Jenny and she was looking at earning enough from the show and speaking engagements to open that school.

Her mechanic, William D. Wills of the Curtiss Southwestern Airplane and Motor Company departed with her new plane from Dallas Love Field, bound for Jacksonville, Florida. Unfortunately, the plane was found to be in such bad condition that it had to make two emergency landings on the way out due to engine troubles. The engines, which in good condition would make 90 horsepower, made what was believed to be two-thirds of that.

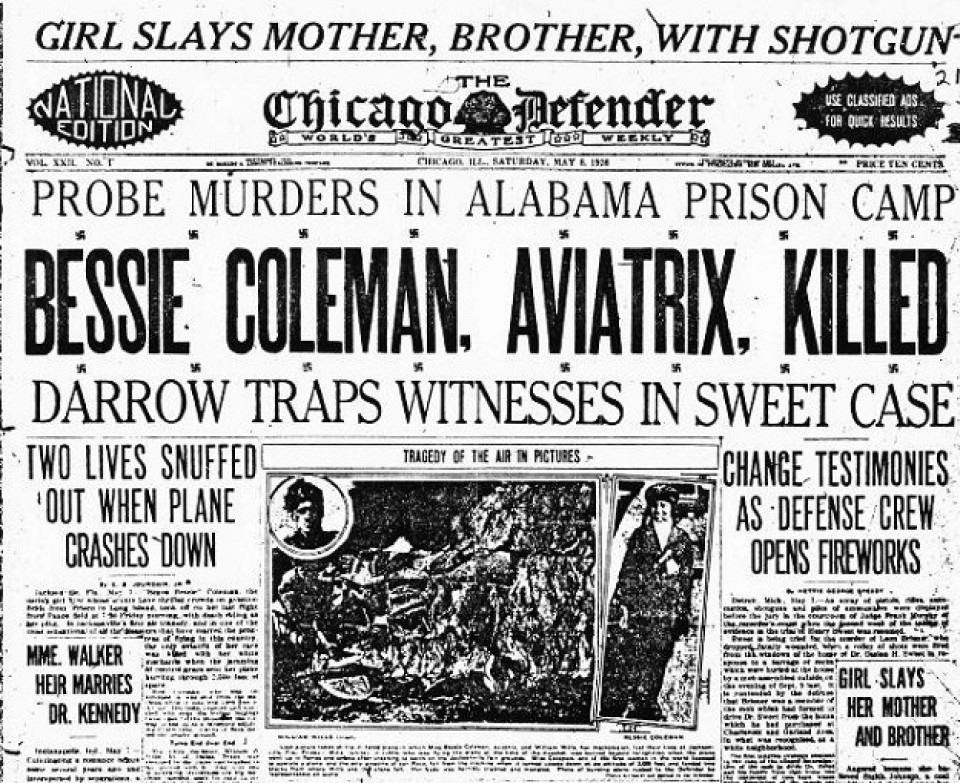

Coleman met up with the Chicago Defender's Abbott one more time before the show. Some say that during this meeting he warned her not to do the show. But that — if it happened — didn't deter Coleman and the next morning she met with Wills and took to the sky. Only minutes into the flight and at 3,500 feet, the National Air and Space Museum notes, Coleman's aircraft entered a steep dive. At 2,000 feet, the aircraft rolled over and she was thrown out, falling to her death. Wills also perished in the crash.

Life After Death

Even in death, the Smithsonian notes, she couldn't avoid racism. While her death headlined at the Chicago Defender, mainstream white news could only focus on her white mechanic. Worse, Coleman wasn't able to open her school.

Her amazing and inspirational life and career may have been ended far too soon, but her legacy continues to this day. Her dream of a Black flight school was realized when Lieutenant William J. Powell established the Bessie Coleman Aero Club in Los Angeles in 1929.

The Aero Club brought opportunities to Black people, including some who would become Tuskegee Airmen. The National Air and Space Museum credits her life and work as opening the skies for the likes of 1930s Black pilot Janet Bragg, the first Black woman in space Mae C. Jemison, Women Airforce Service Pilots and so many more. Pilots throughout history to today note Coleman as one of their inspirations and heroes.

Bessie Coleman achieved what many told her was impossible and not for Black people. In determination to never accept the answer "no" she paved the way for people of color to enjoy the miracle of flight. Coleman overcame hate to pave the way for aviators.

I first learned of Bessie Coleman in elementary school. Then, like many Americans, I rarely heard of her feats again. That's a shame, because in researching this story I learned so much more than the sanitized version that we were told in school. Her story is not just an inspiration for everyone, but also an example of how far we've come.

As I slowly build my own flight hours, Coleman's story sometimes keeps me steeled in my determination in my own dream to take to the skies. Today, people like myself can learn to fly and can in part thank a Black woman who earned her license over a century ago for the ability to do it.