Bentley's Most Famous Car Sucked At Winning

Whenever someone very boring strikes up a conversation with you about an old race car, without fail they will always bring up said car's racing victories. In motorsports, winning is really all that matters—it's largely what validates a car's existence and its ensuing fanbase. So it's weird why one of the most famous, iconic Bentleys ever made—the 1929 4½ Litre Blower Bentley—also happened to be one of the automaker's biggest failures.

(Full disclosure: Subaru invited me to attend the 2019 Goodwood Revival on its dime, where I was able to see some of these old Bentleys for myself. It paid for my flights, put me up in two very nice hotels, fed me, provided all the booze I could want and helicoptered me to and from all three days of the Revival.)

The idea of winning is so ingrained in how we value cars that we now only really talk about certain cars because they'd won. The Porsche 917. The rotary-powered Mazda 787B. The Alpine A110. The Hudson Hornet. The McLaren F1. The Bugatti Type 35. It's not that these cars are inherently uninteresting by themselves, it's just their victories make them all the more significant.

As for the cars that came in third, fourth, fifth, sixth? The cars that ended in a DNF? Not a huge topic of discussion, generally, unless they were spectacularly weird.

That's what makes the famed Blower Bentley so interesting. It's a car that never won any of the races it entered, yet it still enthralls fans everywhere to this day. And its story is one that begins with caution.

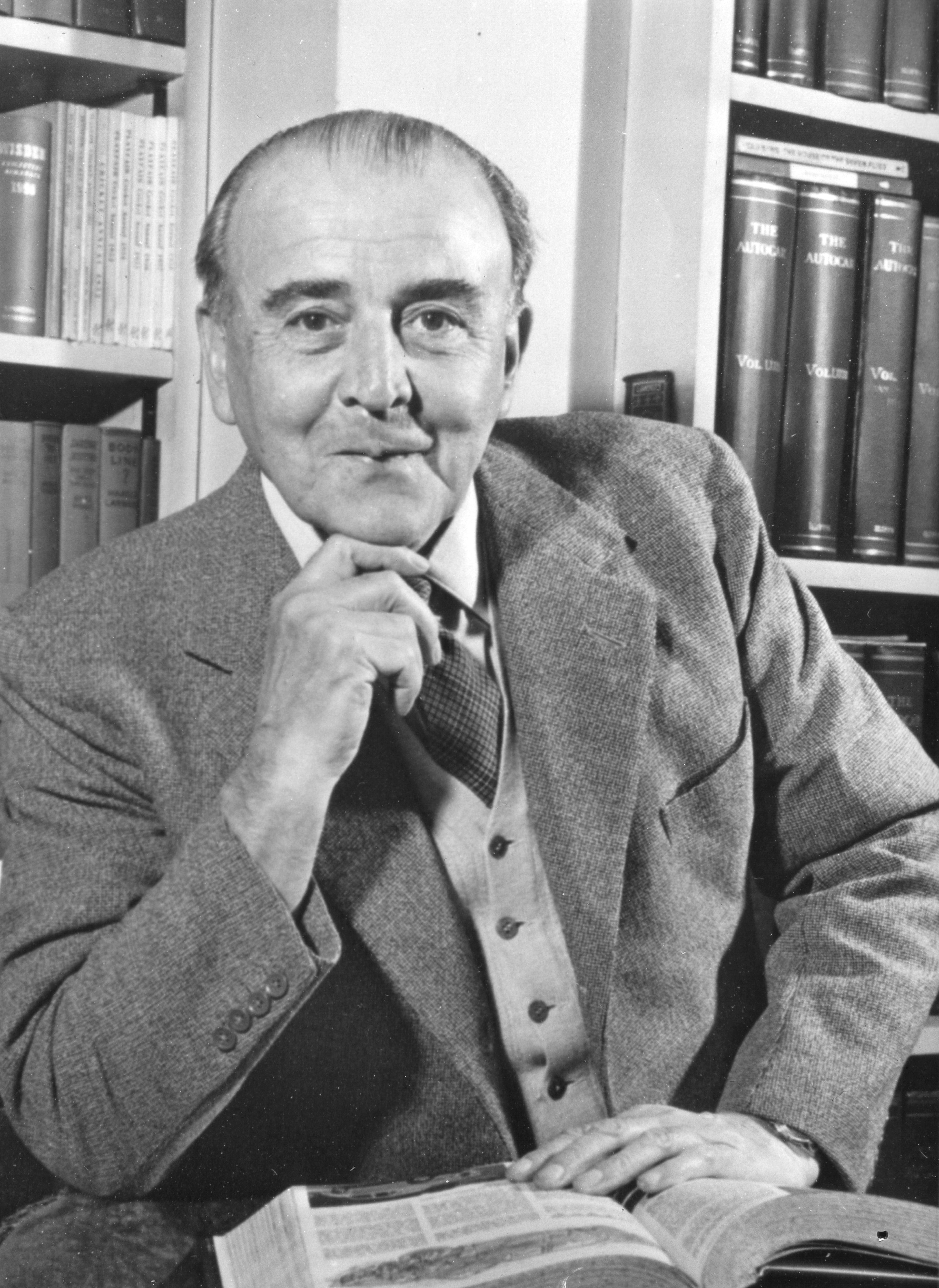

Bentley celebrates its 100th anniversary this year, with beginnings in 1919 by Walter Owen "W.O." Bentley. After a brief stint in the Royal Naval Air Service during World War I, W.O. was awarded some money for his contributions, which he put toward starting his own car company.

W.O. was one of the greats when it came to designing engines in this era, and the cars and engines that bore his name quickly established themselves. What he thought about the Blower... well, I'm getting ahead of myself.

Bentley's first big success was the 3 Litre in 1921, which won the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1924 and 1927. W.O. went on to build the six-cylinder 6½ Litre in 1926 and the four-cylinder 4½ Litre in 1927. But by 1928, despite winning Le Mans that year, the 4½ Litre was nearing the end of development.

W.O.'s solution was straightforward. He used the bigger-displacement 6½ Litres to again win Le Mans in 1929 and 1930 and even had the plans for the upcoming 8 Litre sketched out before it hit production.

It was around this time when Sir Tim Birkin, a very prominent Bentley race car driver, had some ideas of his own.

See, W.O. had always liked increasing power by upping displacement, hence the steady increase of displacement in his racing cars. But Birkin wanted more power for the 1929 season and was very taken by the idea of supercharging. W.O. "bitterly opposed" this and was quoted as saying ominously, "To supercharge a Bentley engine was to pervert its design and corrupt its performance." It seems like the man had some foresight here.

Yet, W.O. didn't exactly have much say in things anymore, as he had lost financial control of his company to diamond fortune heir, Woolf Barnato, three years prior. Barnato, a racer himself, green-lit the supercharging project.

Birkin sought out Amherst Villiers, a British engineer with an incredibly French name, and the Roots-type supercharger he produced. In 1929, Birkin commissioned the production of a series of supercharged, 4½ Litre Bentleys. The engineers were able to increase the power from about 130 brake horsepower to 240 BHP in race trim.

Of the cars, W.O. wrote, "It was, I thought, the worst thing that could happen to us. They would still be Bentley cars, carrying with them the spurious glamour associated in the public's mind with the supercharger. I feared the worst and looked forward to their first appearance with anxiety," according to a wonderful Automobile feature from earlier this year.

Racing regulations of the time stated 50 of the "Blower Bentleys" had to be made in addition to the five meant for racing. Birkin was able to secure funding from a very rich heiress named Dorothy Wyndham Paget, who was known in Britain as a famous owner of racehorses.

Bentley includes a highly enjoyable snippet of her on one of the company archive pages:

She was also highly eccentric; in later life she became entirely nocturnal, eating breakfast at 6.30pm, lunch at 10.00pm and a large dinner in the early morning. But as a young woman in the late 1920s, a visit to Brooklands kindled her interest in motor racing. She took driving lessons from Tim Birkin and, it's claimed, competed under the pseudonym 'Miss Wyndham'. Birkin described her as one of the finest women drivers of fast cars he had ever come across. Without her sponsorship, the Blower Bentley would never have entered racing legend.

As with everything in life, if you can't afford it yourself, you find a rich friend to afford it for you.

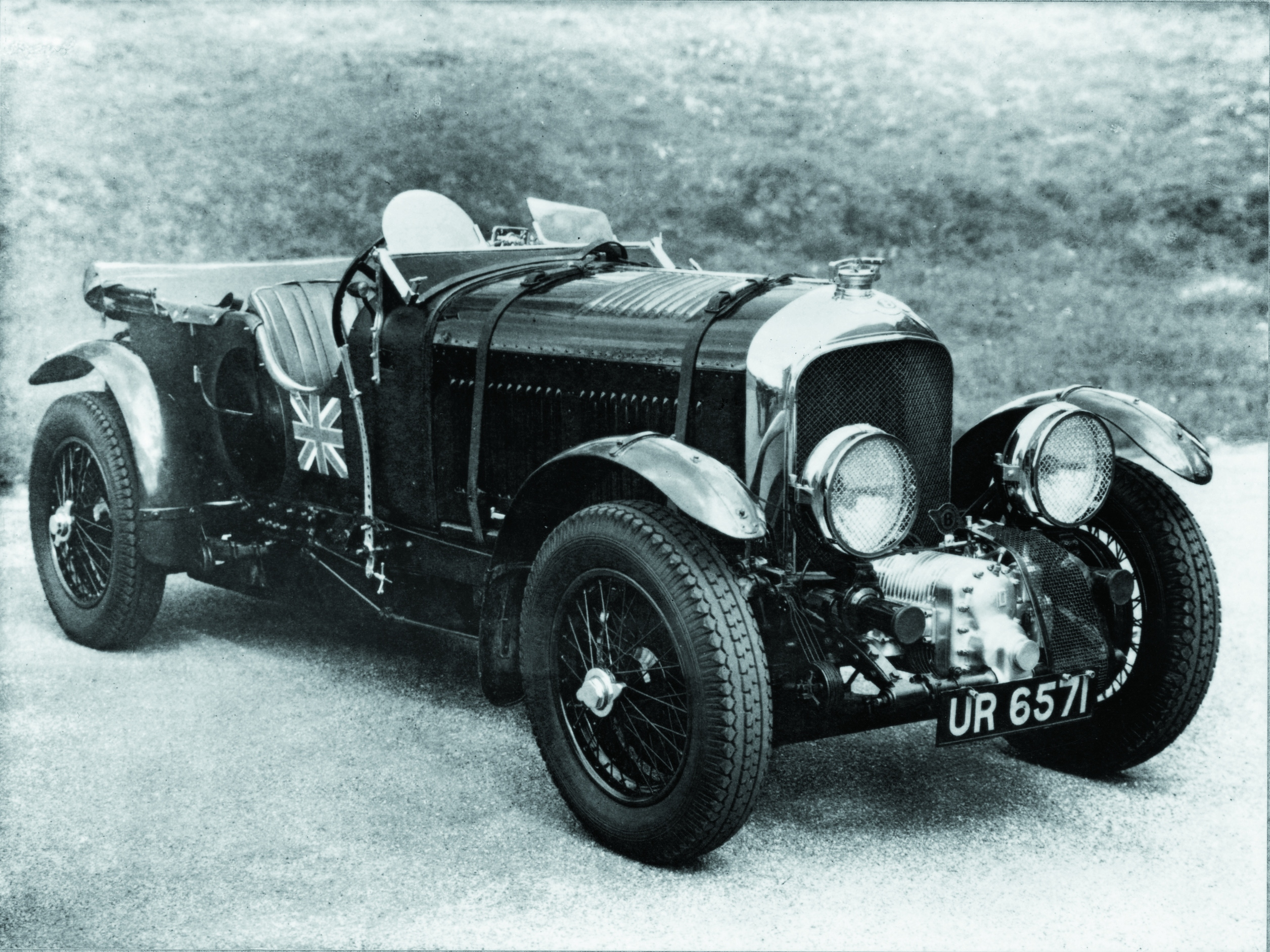

The resulting cars had a striking look. Because the supercharger had been added as an afterthought, it wasn't an inherent part of the car's design like the Bugatti and Mercedes-Benz racers of the era. Rather, the blower stuck out in front of the crankshaft, nearly level with the car's own headlights.

The cars were, in a word, huge. They were 172 inches long (about 14 feet) and weighed about 3,583 pounds, according to Hagerty. They would dwarf many modern crossovers today.

Unfortunately, the Blowers were unable to achieve the very thing they were designed to do, which was win races. The cars for Birkin's independent team were not ready for the 1929 Le Mans event, and for the rest of the races they were regularly plagued by breakdowns, unable to even finish at Brooklands during the Six Hour Race.

"Thereafter it was a disheartening tale of mechanical malady," wrote a Motor Sport Magazine story from 1989:

... lightened only by some less than satisfying results (Birkin was third and fourth in 1929 and 1930 respectively in the Irish GP) and the spectacular achievement in the French Grand Prix at Pau in 1930 when Birkin drove his greatest race against a field of purpose-built racing cars to finish second behind Etancelin's Bugatti. Another second on handicap (Hall/Benjafield) in the Brooklands 500-Mile race later that year was the final official outing for the team (by now backed financially by Birkin's cousin, the Hon Dorothy Paget) which had placed in six of the ten races entered, but failed to achieve a victory.

"Failed to achieve a victory." After all that trouble, the Blower Bentley never won a race.

Still, that didn't mean the cars weren't fast, because they were. A Blower Bentley set a lap record at the Brooklands course. They were just monstrously unreliable and apparently loved to understeer because of their gargantuan weight in the front.

No, the Blowers made their name in other ways. An interesting tidbit from the 1930 Le Mans depicts Birkin and Mercedes-Benz driver Rudolf Caracciol racing deadlocked, when Birkin was finally able to pass the Benz on the Mulsanne Straight, albeit with two wheels on the grass. Both cars didn't end up finishing, which left Woolf Barnato to win in a racing-spec 6½ Litre, the Bentley Speed Six.

Post-race myths claim Birkin wound out the Benz on purpose by using a "tortoise and hare" technique, with the Blower being the faster and less reliable competitor but the Speed Six winning by being slow and steady. However, Bentley now says Birkin was probably trying to win and was just driving the only way he knew how: flat out. Maybe if he hadn't, the car wouldn't have broken. As for the Blower, Nobby Clarke, who was Bentley's racing manager in those days, merely said, "The Blower eats plugs like a donkey eats hay."

W.O., likely with a twist of equal parts I-told-you-so attitude and shame, savagely wrote, "The supercharged 4½ never won a race, suffered a never-ending series of mechanical failures, brought the marque Bentley disrepute and, incidentally, cost Dorothy Paget a large sum."

He went on, "It is a sad story, with a sting in the tail. Because Tim managed to persuade fellow Bentley Boy, diamond heir, and company financial savior Woolf Barnato to allow him to enter a team in the 1930 Le Mans (in which none survived), we were obliged, in order to meet the regulations, to construct no less than 50 of these machines for sale to the public."

Separately, the stock market crash of 1929 hit Bentley hard. It's unclear how much the strain from those 50 cars contributed to Bentley's woes during the Great Depression, but Motor Sport reports many were discounted and passed back and forth between dealers because nobody bought them.

In 1931, Bentley was taken over by its rival, Rolls-Royce. W.O. left his namesake company right after his contract expired in 1935 and went on to work for Lagonda, helping to build a line of cars that were "Bentleys in all but name."

I do find myself feeling a little bad for W.O. He seemed to be against the Blowers from day one, but they wound up being some of the most exemplary and eminent Bentleys ever made. In Ian Fleming's novels, even James Bond drove a 1931 Blower Bentley.

To see these hulking behemoths of cars in person today is a sight to behold. At this year's Goodwood Revival, the Brooklands Trophy race was comprised entirely of Bentleys, all built in or before 1930.

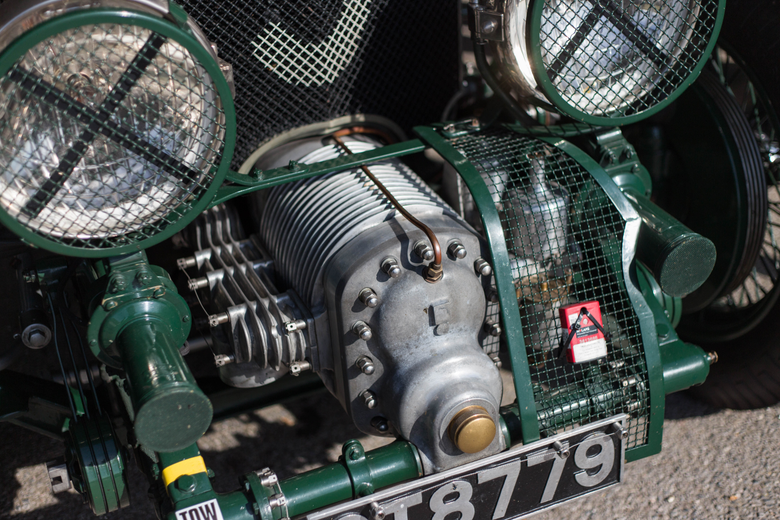

My eye was especially drawn to a deep green, 1930 Bentley 4½ Litre "Blower" parked in the paddock. Like the famed Blower Bentleys I'd read all about, this car also had its supercharger mounted way the hell out in front of its own engine compartment and also had Vanden Plas Le Mans-style tourer coachwork.

That day, the car was being raced by Gregor Fisken, a British race car driver and businessman who started a historic car dealer in London called Fiskens. Needless to say, he knew quite a bit about what he was driving.

Though it isn't one of the original 55 Blower Bentleys (rather, it was the 664th out of the 665 regular 4½ Litres produced), Fisken told me it had been supercharged "in more recent years" following the style of the old Blowers. Looking more closely at the supercharger on the nose, it appeared to have two SU carburetors of its own, something I'd never seen before.

"The supercharger has its own SU carburetors because the supercharger sucks the petrol from the carburetor and then compresses and supercharges the air and petrol mixture," Fisken explained via email. "It then pushes that mixture directly through a manifold into the engine combustion chamber. There are no other carburetors on the engine."

Keep in mind the regular Bentley 4½ Litre did manage to nab a win at Le Mans. The Blower did not. But it was still the Blower the car's owner chose to imitate, not the non-supercharged 4½ Litre. Something about that car made someone alright with dropping a lot money to create a tribute.

Watching these big Bentleys hurtle through the circuit's chicane was both exhilarating and terrifying. The cars are so tall and they lean over so much it's a wonder none flipped over.

Very little in the way of similarities exist between the vast, pre-war Bentleys and the sleek machines of today (except maybe their weight). Bentley is as old an automaker as any, but obviously it has to keep with the times. It's difficult to imagine any one Bentley nearly ruining the whole company today, though. Especially with the Volkswagen backing.

W.O. got it both right and wrong. He was correct in fearing the Blowers would never win. But he was also mistaken in thinking the cars would bring the company disrepute. Despite their lack of racing victories, the Blowers remain among the most influential and treasured Bentleys to date. They were where refinement and ambition met and it's not difficult to see why the resulting car is so captivating now, 90 years later.

Victory is but one path to mystique. And anyone with eyes, ears and a sense of touch will understand the Blower Bentley's enduring presence.