An Ancestor Of All Internal-Combustion Vehicles Was A Moss-Powered Jet Ski Built By The Inventor Of Photography

I have to admit, while I know that's a fairly cumbersome headline, I really like just how much is packed in there, and, even better, it's all true. The very first internal combustion to actually power a vehicle was, at least in part, fueled with a type of moss, and that engine powered a boat that worked on the same principles as a Jet Ski, and, yes, the person who developed it later went on to take the first ever photograph. Sometimes the world is just delightfully weird like that.

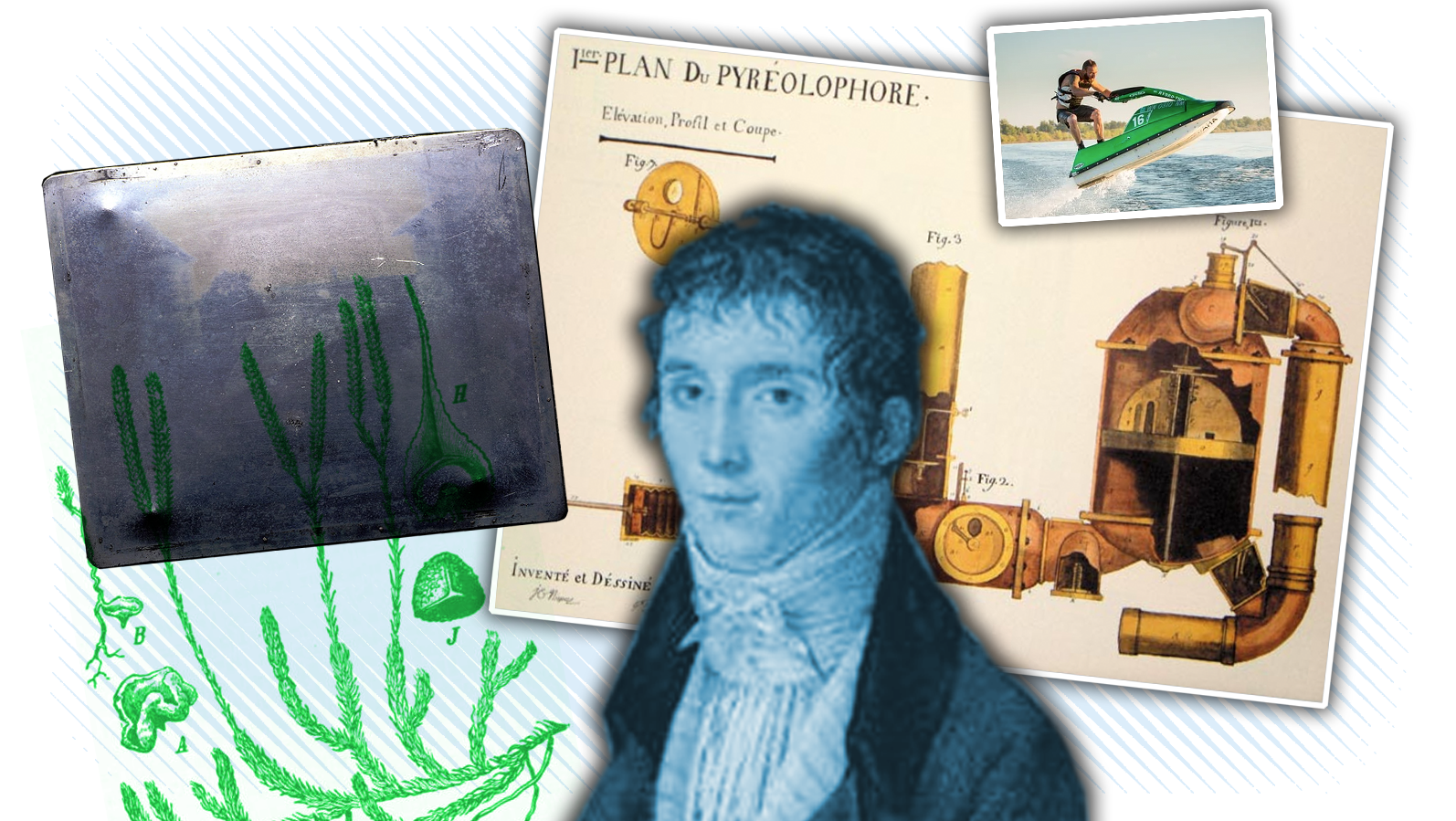

It was a pair of French brothers with the last name Niépce, Nicéphore (the one who later made the first photograph) and Claude, who developed this first internal combustion engine all the way back in 1806. They called their machine the pyreolophore, because of this linguistic word-segment chain: pyr=fire, eolo=wind and phore=carry or produce.

The fuel used by the engine was a mix of Lycopodium powder (clubmoss spores, which combusts when dispersed in a cloud), along with some fine coal dust and resin.

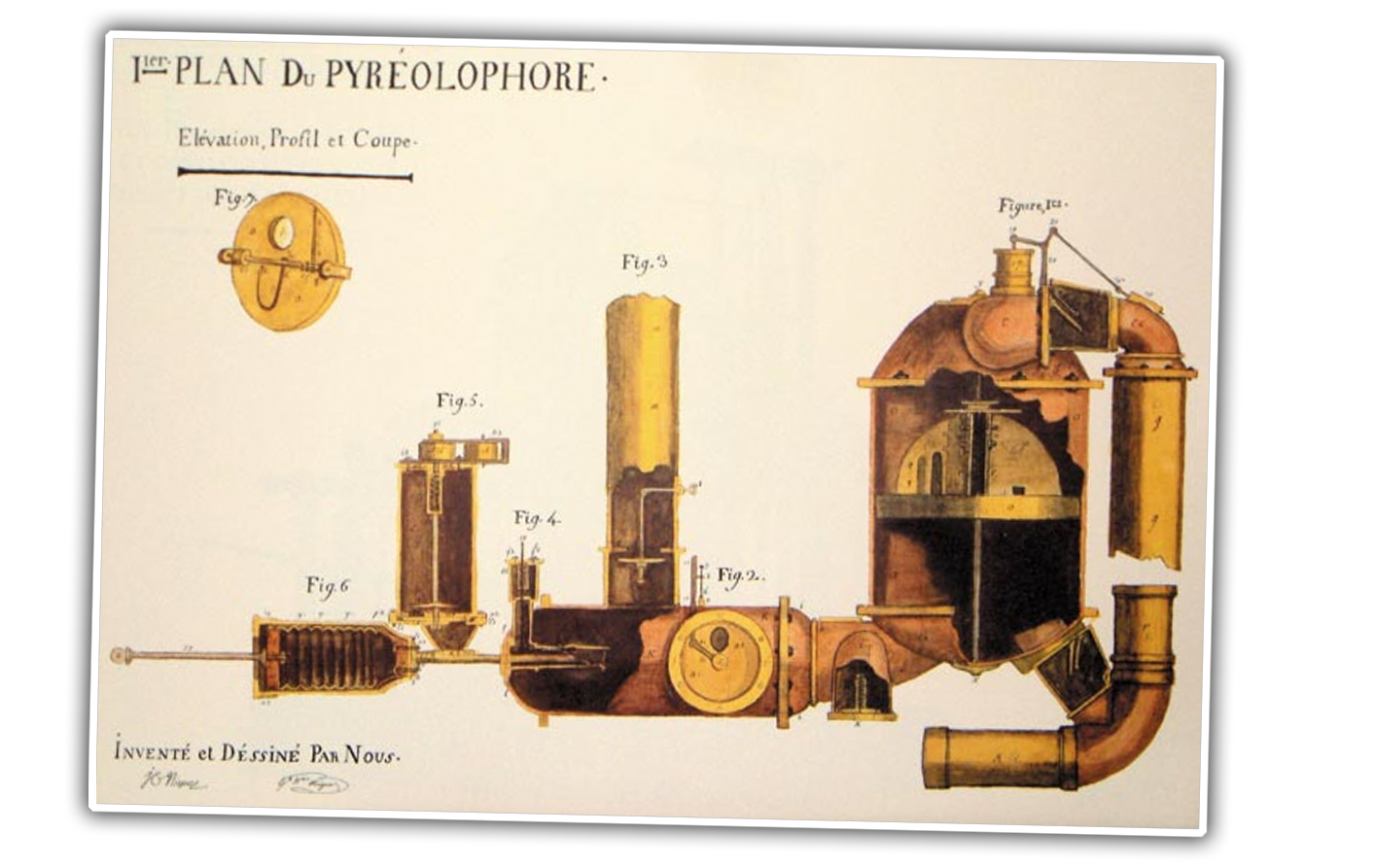

The brothers described their machine in their 1807 patent as "a new Machine whose driving principle is air dilated by fire."

That "dilated" air expanded to move a piston, though the layout is quite different than a crankshaft-based four-cycle engine as we know it today. The operation of the engine was described in 1824 by Sadi Carnot, the one who came up with the Second Law of Thermodynamics, which demonstrated an upper limit to the efficiency of heat to work in a heat engine.

Carnot described the engine in his book called Reflections on the driving force of fire and the machines proper to develop this force, which sounds like a real page-turner, with sections like this:

Among the first attempts made to develop the driving force of fire through atmospheric air, we must point out those of M.M. Niépce, which took place in France, many years ago, by mean of a device called pyreolophore developed by the inventors. This device consisted of a cylinder, with a piston, where atmospheric air was admitted at normal density. A highly flammable substance was projected at a very high level of fineness, and that remained a little while in suspension in the air, then it was ignited. The ignition caused an effect almost as if the elastic fluid had been a mixture of air and a flammable gas, like air and carbonaceous hydrogen; there was a sort of explosion and a sudden dilatation of the elastic fluid, dilatation that used to act entirely on the piston. This one would be set in a motion of a certain amplitude, and the driving force was thus created. The operation could be restarted by renewing the air and going through the cycle again.

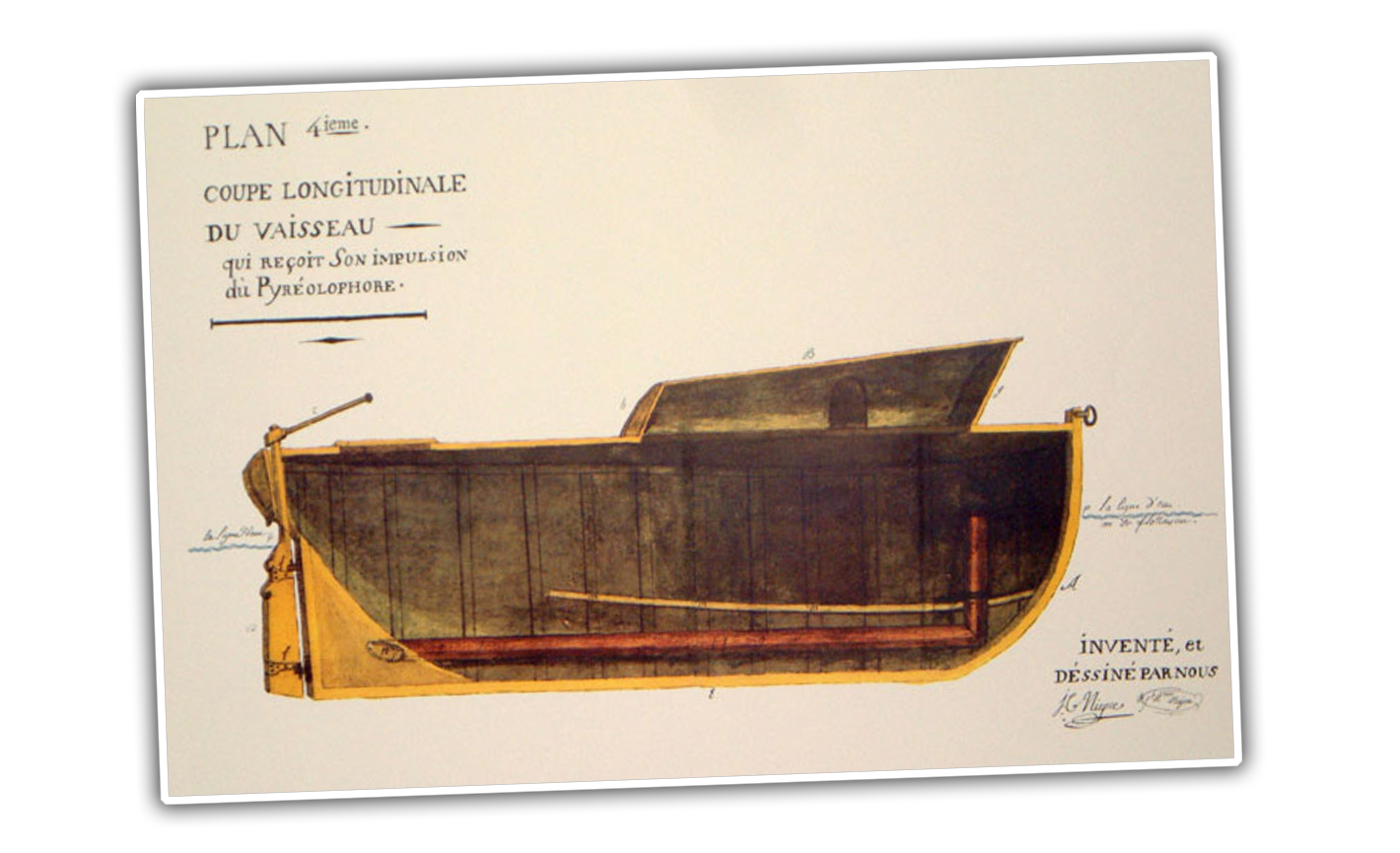

In practice, the pyreolophore was not connected to a crankshaft to drive a propeller when it was installed on a boat in 1807, but rather operated more like a Jet Ski, with the sucking and ejecting forces from the piston used to draw water in the front of the boat and eject it out the rear.

This first motorboat also appears to be the first vehicle powered by an internal combustion engine, though De Rivaz' hydrogen-powered internal combustion car appeared the next year, in 1808 (though some sources state 1807, as I did here).

Incredibly, the brothers Niépce also seem to have invented the concept of fuel injection, skipping the carburetor stage entirely, as they sought out a fuel better and cheaper than the pricey but very flammable moss spores.

First proposing the idea in June of 1816, Nicéphore wrote to his brother about using kerosene as a fuel, and in July of the next year, after much testing by Claude, the idea of fuel injection was proposed:

"As a matter of fact if you succeed in injecting white oil of petroleum with enough energy to get instant vaporisation, it is sure, my dear friend, that you should obtain the most satisfying result."

We're still using that "satisfying result" in engines today. Some of their tests were remarkably simple, blowing fuel through tubes, using their tongues as valves:

"The part through which he had to blow was about 66 cm long and the one through which the oil would flow was about 33 cm. The exhaust was beveled as in the preceding experiment.

This was completely successful: "The flame, compared to the small amount of oil used, was enormous; it was intense, instantaneous, and detonated like lycopod", Nicéphore said, and added: "the results that I just got, have rekindled my courage and fully satisfy me."

Their engine was still a long, long way off from the Otto-cycle engine that would eventually come to dominate the world, but the start was very clearly here.

Nicéphore and Claude spent the next two decades refining and promoting their engine, but by 1813, Nicéphore began to become interested in lithography, which led him down the path that would eventually result in the first photograph in 1826.

Using a simple camera lucida (basically a box with a tiny hole—a pinhole camera) and a pewter plate coated with a bitumen-based solution, which he exposed to the light from a view out his window for about eight hours.

He then washed the plate with a solution made from oil of lavender and kerosene (white petroleum), creating a permanent positive image on the plate.

As you can see, the image quality isn't, um, great, but it worked, and proved that light could be "captured" as an image in a permanent way, which paved the way for all photography to follow.

It's all pretty incredible, really, that one person could have been at the origins of two such huge and wildly different human achievements, but there it is. And, moss and Jet Skis are involved, which, as always, makes it all even better.