A Memoir Of The World's Biggest Marussia Fan

I can't remember exactly when I decided I was going to become a Marussia Formula One fan, but I'm fairly certain it all started as a joke. Oh man, I surely laughed to my friends, what if I became a fan of the backmarkers? Haha, funny joke, Elizabeth! You just signed yourself up for several years of pain and disappointment!

At the start of the 2014 F1 season, I was still relatively new to the whole "European racing" thing and hadn't sworn any undying allegiances to a team. But my mom surprised me with tickets to the US Grand Prix as an early eighteenth birthday gift, so I figured that this was as good a time as any to find something to give a shit about. As I set my alarm to wake up for the first race in Australia, my options were vast.

And yet I ended up with Marussia.

Marussia will tell you everything you need to know about the little teams that fill up an F1 grid, the big names and small budgets that exist behind Ferrari, McLaren, and whatever other auto manufacturer that's dumping cash into winning titles at the moment. The team that I knew as Marussia entered F1 in 2010 under the name Virgin Racing, as the BBC notes, something that's typical for teams major and minor. You start as one brand, finances change, and you swap names. Mercedes today was Brawn yesterday and Honda before that. Red Bull Racing was Jaguar and Jaguar was Stewart.

It wasn't until 2012 that Virgin rebranded with its more familiar Anglo-Russian name. It was the year test driver Maria de Villota lost an eye in a bad crash that, a year later, turned fatal. It never really felt like the team was able to shake off that dark mark in its brief history.

And that's not really all of the weird shit Marussia got up to. There was that attempt at building a supercar that dissolved in 2014 but also briefly included a showroom in Monaco, that haven of clean money and upstanding characters. All the while, its F1 venture was just a revolving door of drivers equipped with good sponsorships or heaps of their family's money as a way to just keep the damn thing in business, even though Marussia was a solidly second-to-last place team at best. It was one of those teams that always came across as a little shady and mysterious, possibly only because nobody really cared enough to ask them how they were doing.

My logic at the time was very much of the "well someone has to love them" line of thought. Marussia and Caterham were the butt of so many jokes—if anyone actually remembered they existed long enough to crack one. Honestly, the only reason I ended up opting for Marussia was because I prefer the color red.

I kind of liked Marussia's whole deal, honestly. It felt like everyone on the team was there less for the money and more just because they really fucking liked to go racing. Marussia wasn't the center of bitchy Ferrari-type drama, it didn't have McLaren's history, it wasn't a glitzy party center like Red Bull, it certainly would never be as fast and professional as Mercedes, and it also didn't try to crowdfund its team back into existence like Caterham did. All in all, it was an ethos I could get behind, even if only jokingly.

But I should have known that what started out as a joke would quickly turn into my reality. Like ironically saying "y'all" enough that it becomes part of your everyday lexicon, so too did my decision to become an ironic fan turn into a genuine, heartfelt desire for this team to achieve the very best they could.

If you've never been a desperate backmarker fan before—especially in Formula One—I cannot even describe to you how badly it sucks. Oh, so you actually want to see your favorite driver on TV? Hah—maybe you'll get a chance when they're getting lapped. What are your expectations for this race? Okay, lower them. No; farther. Keep going. There, good! Don't let yourself ever hope for anything better than maybe one driver finishing a race. Now you want branded merchandise? What the hell is merchandise?

Rooting for the backmarker team is a lot of, "dear god, please let me drink away this pain" and tweeting "Yay! We finished a race!" while everyone else is celebrating a win. It's a lot of DIY and hoping for the mediocre best while also expecting the worst. It's praying, please, for the love of all that's holy, just let them score a single point this year so the team can have a slightly larger cut of the prize money than usual and maybe end up getting to develop that one part they had to write out of the budget this year.

It's wonderful and beautiful and terrible and joyful and heartbreaking and maddening and amazing all at the same time. And I learned that fully as 2014 progressed.

Because 2014 was the year Jules Bianchi got points.

The Monaco Grand Prix: the premiere event in the Formula One calendar. One-third of the coveted Triple Crown, alongside the Indianapolis 500 and the 24 Hours of Le Mans. It's also one of those races that either really sucks or kicks a large amount of ass. And that year, it kicked ass.

Sergio Perez spun his Force India. Adrian Sutil crashed his Sauber on lap 24 and took Kimi Raikkonen out of contention, causing him to finish a lap down. Esteban Gutierrez, Valtteri Bottas, Jean-Eric Vergne, Daniil Kvyat, Sebastian Vettel, and Pastor Maldonado also didn't finish the race. And so Jules Bianchi finished ninth. He scored not one but two points.

Racing fans subsequently lost their shit. I remember Twitter just absolutely blowing up. It was the first time I ever remember crying because of a race result. And it further secured my love of the Marussia team. So many months of disappointing results, and now: success. Shit... that felt good! Good results were awesome! I could see why people were actually fans of winners!

I started really gearing up for the US Grand Prix at that point. It would be my first ever race, and I wanted to go big. I thought about making t-shirts. I definitely knew I wanted to paint a banner or a flag or something in support of the team. And I was getting hyped about trying to nab a selfie or two during the autograph session, because Bianchi had firmly cemented himself as my favorite driver on the grid.

And then the Japanese Grand Prix happened.

To say I was devastated would have been an understatement. I felt hopeless. It felt pointless to go to the race. What if it happened again? What if nothing happened, but the whole race was overcast with the gloom of morbidity? What could I even do?

I'd already purchased a French flag, intending to paint something aspirational on it for Jules. Instead, I decided to cover it with the names or Twitter handles of anyone who messaged me on Twitter in the wake of Bianchi's accident. I didn't know how, but I was going to try to get that flag to Marussia. And I decided I was going to be their biggest fan—unironically this time.

As it turned out, Marussia withdrew from the US GP. There was nowhere for the flag to go. I held onto it until the Canadian Grand Prix the following year, when I was finally able to give it to the team during a pit walk.

...We wanted to say a huge thank you to @elizabeth_werth for delivering this incredible flag bearing 3000 signatures! pic.twitter.com/k3dKkmDvJC

— Manor Racing (@ManorRacing) June 5, 2015

Bianchi's accident changed something for me, and I'm still not totally able to define exactly what. It was a fork in the road, and I had to choose whether I'd stop watching racing or instead throw myself into it with a wholehearted passion. It was the first time I ever wrote something about motorsport (minus the childhood essay I wrote on Mark Donohue). My heart clicked into gear. Come what may, I was going to stick it out as a race fan.

And that meant I just went doubly hard for Marussia. I would not only be a fan. I would become the world's biggest Marussia fan.

Then the team went into administration. I spent all winter massively heartbroken, thinking I was never going to see Marussia race again.

But as soon as they emerged from the grave and signed Will Stevens and Roberto Merhi, I geared into action. I was going to travel the world to watch Manor Marussia race in multiple countries and multiple continents. Who cares if I was just a college student with only my high school graduation cash tucked away in savings? I was going for it.

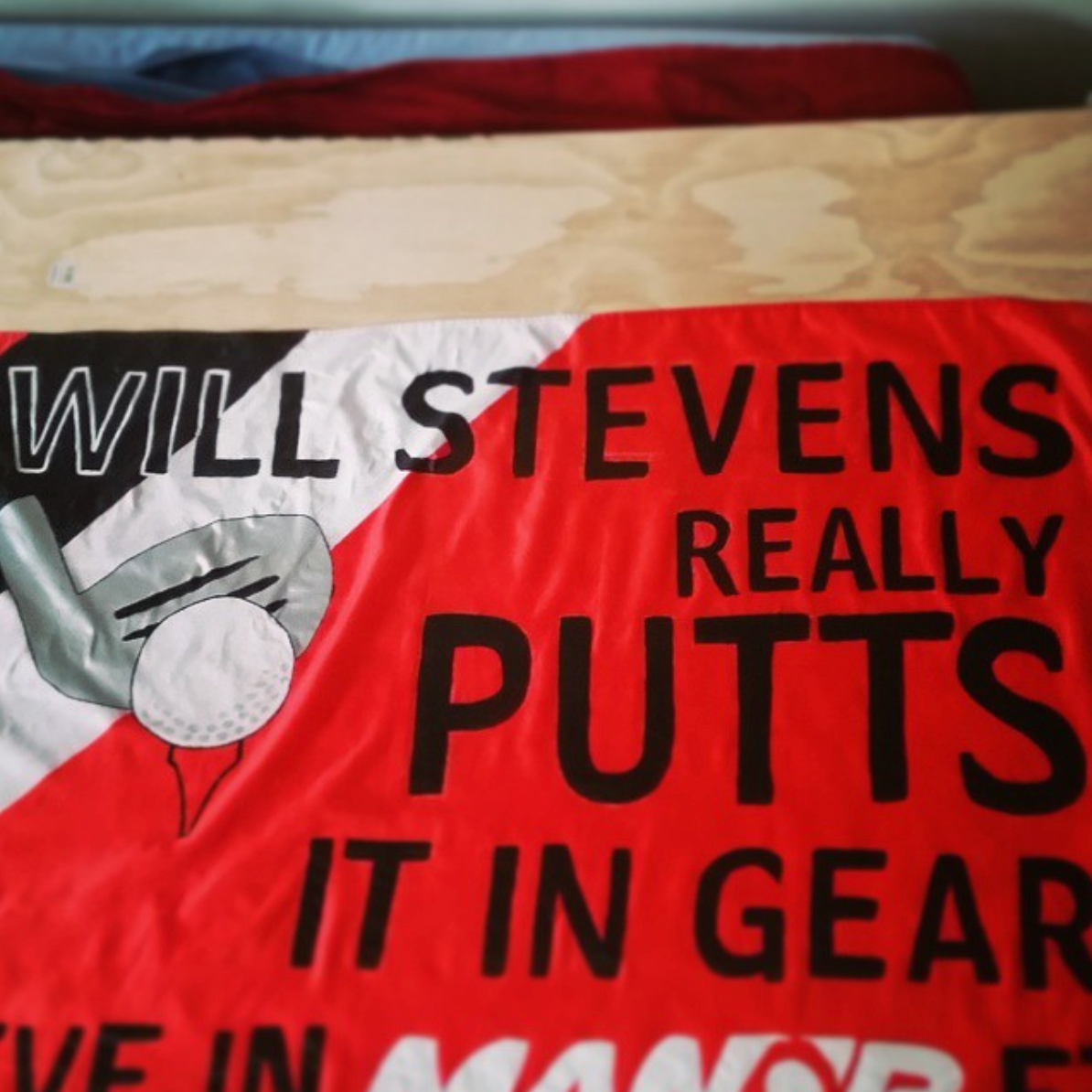

I messaged friends online—some that I'd met, some that I hadn't—and asked if they'd like to travel the world with me. I wanted to go to F1 races Canada, Austria, Germany, England, and America (although Germany ended up getting scrapped when the GP was canceled). Who cares if I was traveling around the globe with a bunch of strangers, painting flags in my spare time, sleeping on the ground, and nursing hangovers in the presence of loud cars? This is the price I would pay to show Marussia some love. I had missed them racing once already, then thought I'd never see the cars on track again. I was not going to miss this opportunity.

Yes. I was actually doing it. I was spending all my money to travel around the world supporting... the worst Formula One team on the grid.

I'll spare you the gory, mushy details about what a wonderful, life-changing experience I had. But it was genuinely incredible. Pretty much all my best tips from the Race Car Survival Guide came from all the wonderful, terrible mistakes I made on that trip. I made great friends who did not care one single bit about Manor Marussia but also didn't treat me like I was an extreme wiener for showing up to the British Grand Prix with two (2) hand-painted Will Stevens flags. I ended up befriending the team's chief executive officer (i.e. we were on a first name basis, not like... hanging out on off weekends) Graeme Lowdon, who turned out to be very polite and seemed delighted that some weird American girl was following the team around to all the races—who still gave me tours of the Manor WEC garage when the series came to Austin. I was the first person to receive a Manor hat—long before they were given out for free and sold at the track.

It was absurd, but I'd firmly wedged myself into a very specific little niche and realized that I was desperately in love with the whole concept of open-wheel racing. And it turned out to be even better when Alexander Rossi—then an American GP2 driver who was stoked we all turned up in Austria with flags and banners painted for him—got signed to Manor Marussia.

My friends and I lost our shit.

That year, the 2015 US Grand Prix, was the year it downpoured. Saturday was pretty much cancelled, but my friends and I showed up at the track decked out in our Manor gear anyway, kindly heckling the team from the front stretch grandstand. When officials decided to reward those of us who stuck it out for a qualifying that never happened with a pit lane walk, Graeme Lowdon pulled us up to the garage and actually let us touch the front wing of the car.

When Manor Marussia went into administration again that year and was ultimately bought out by Sainsbury CEO Justin King ahead of 2016, I have to admit that suddenly, the team felt estranged from me. Most of the significant former staff—Graeme Lowdon and John Booth, mainly—left to form a LMP2 team in the World Endurance Championship. Manor Racing in F1 signed Rio Haryanto, Esteban Ocon, and Pascal Wehrlein. The team drastically changed its color scheme. It felt like going away to college and coming home to find that no one told you your family moved and now someone else is living in the old house. I didn't belong here anymore.

I gave WEC a try that year, but endurance racing outside of the year's biggest events just isn't my thing. I swapped my focus to IndyCar, where former Manor driver Alexander Rossi had moved full time, and found another sorta-backmarker team and aspirational driver to follow: Dale Coyne Racing with Conor Daly. I still watched F1 and went to two races that year, but only casually. I didn't really have A Team to follow anymore. When I started writing about racing professionally soon after, I kind of grew more jaded about racing. That very specific, personal passion was gone, as much as I still love motorsport.

But, for as hilarious as it sounds, I still credit one little backmarker team with giving me the overriding desire to actually chase motorsport across the globe and learn that there's nothing I'd love more in the world than to do that for the rest of my life. It led me to a job I love, great friends, and even my husband. Marussia ended up meaning more to me than I would have ever dreamed (or, really, even wanted)—but I've never been so glad an F1 team existed.