A Chain Cut Through A Capsized Cargo Ship Filled With Cars And The Process Is Fascinating (UPDATE W/VIDEO)

Workers used a chain to cut off the first enormous chunk of ship, revealing mangled cars within. Here’s a look at the fascinating way the team pulled this off.

Back in September of 2019, a 600+ foot cargo ship called the MV Golden Ray, which was apparently loaded in an unstable fashion with over 4,000 cars, capsized in St. Simons Sound just off the port of Brunswick, Georgia. Since then, responders have been working to remove the ship in sections to send the hulk to the scrapper. November was particularly exciting, as workers used a chain to cut off the first enormous chunk of ship, revealing mangled cars within. Here's a look at the fascinating way the team pulled this off.

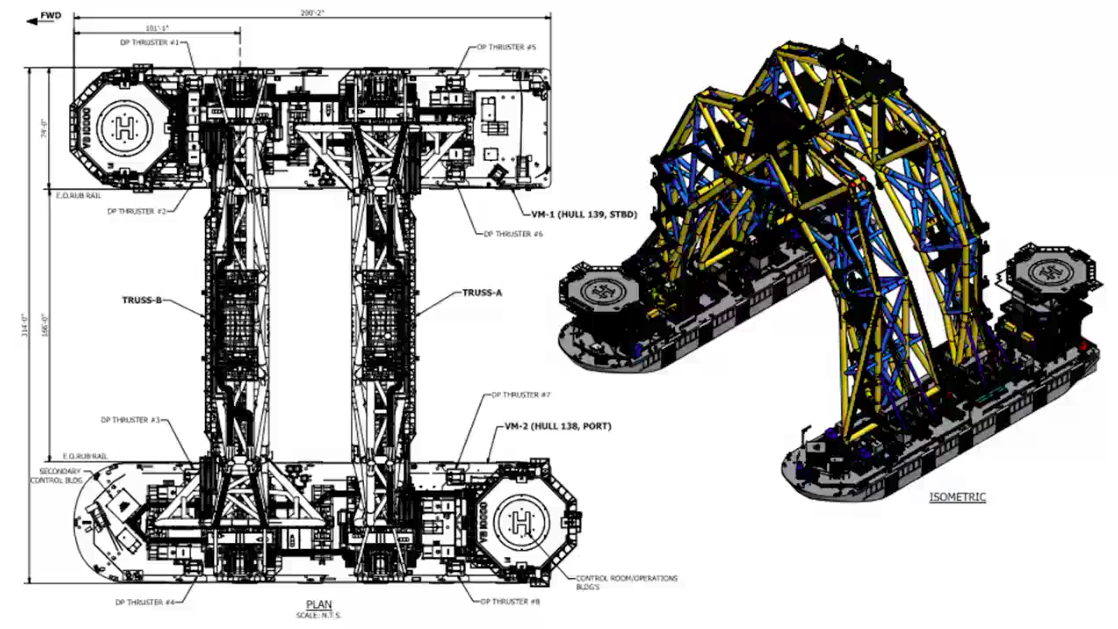

The VB-10000 Lift Vessel

The main player in the complex slicing operation is called the Versabar VB-10000 lift vessel, a gigantic yellow dual-barge crane used for the first time in 2010 and developed in response to hurricanes damaging oil platforms. The company that builds the colossal contraption says capacity of the tall twin-gantries is 7,500 tons, though each of the two trusses is structurally capable of handling over 5,000 — it's apparently the buoyancy of the barges that limits capacity to 7,500. Speaking of the two barges, each has four 1,000 horsepower thrusters to keep the vessel precisely positioned overtop of the wreckage.

Attached to the VB-10000, whose guts you can see in the CAD drawing below, is a pulley system that incorporates a steel chain that runs along the bottom of the sunken ship, and that — thanks to two engines — reciprocates back and forth at a rate of seven feet per minute, yielding a slow grinding/cutting action. Per a representative from St. Simons Incident Response, a team removes links from the chain as the cutting operation advances—this acts to maintain the upward chain tension that cuts through the ship.

Lifting “Lugs”

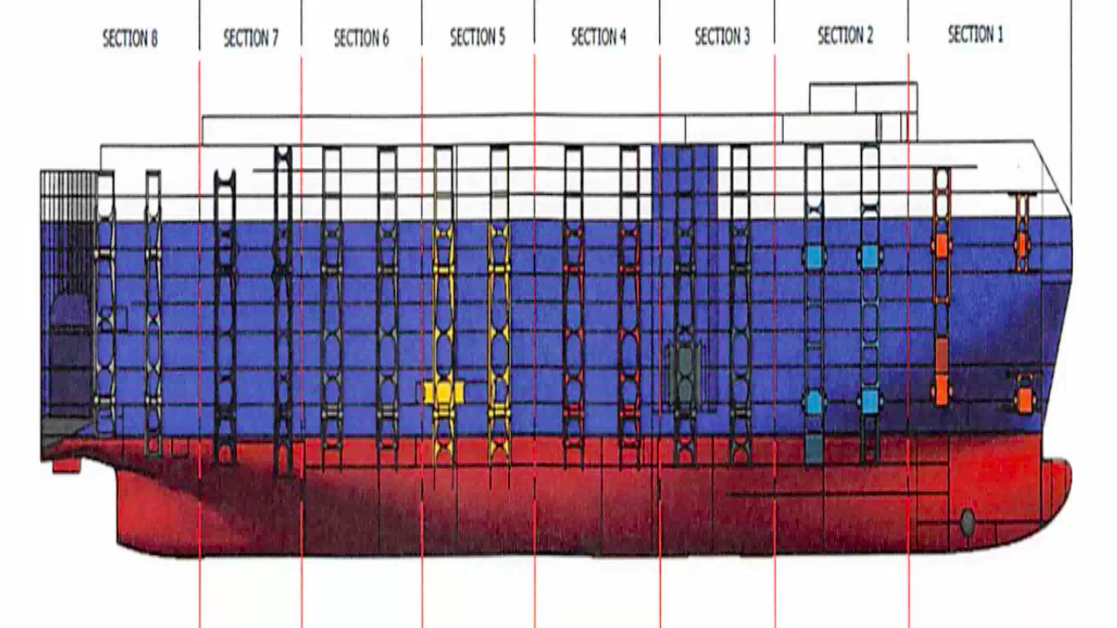

Texas-based contracting firm T&T Salvage is leading the charge, cutting the Golden Ray's hull into eight sections that weigh between 2,700 and 4,100 tons according to St. Simons Sound Incident Response (which is a unified response outfit that includes representation from the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Coast Guard, and a response organization assigned to the Golden Ray—Gallagher Marine Systems, in this case. Many of the photos you see here are from St. Simons Sound Incident Response). The schematic below shows how the ship will be sectioned. The approximate locations of the seven slices are shown in red.

T&T welded custom brackets, which St. Simons Sound Incident Response refers to as "lifting lugs," to each section of the hull.

As shown below, the lugs are enormous (one of them weighs over 38 tons) metal additions that stabilize the ship as the chain cuts through the hull and act as lifting points that distribute the load as the VB-10000 raises the ship onto a barge. The yellow "ropes" used to lift the section from the lugs are "ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene slings," which St. Simons Sound Incident Response says "are as strong as steel at a fraction of the weight."

The two photos below show the scaffolding that acted as platforms for workers as they welded the enormous chunks of steel to the Golden Ray's Hull. Note that it appears that workers actually cut a large hole into the hull, presumably so they could weld some bracing directly to the lug and to the backside of the hull:

The Cutting Operation

The video clip below from Jacksonville local news channel WJXT shows a nice animation of how T&T plans to remove the ship piece-by-piece using a cutting chain, a huge lift vessel, winches, and the lifting lugs.

Here's a screenshot of the most important bit. You can see the crane stabilizing the ship via the lifting lugs, and the chain below the ship, wrapped around the hull so that it can make the cut as it reciprocates. Each cut, per St. Simons Incident Response, was expected to take 24 hours, though as you'll read in a moment, it didn't work out that way, as the bow and stern were apparently stronger than expected, per a representative from St. Simons Sound Incident Response.

The cutting chain is 400 feet long, with each 80-pound link stretching 1.5 feet from end to end and having a thickness of three inches. The photo below of workers inspecting the chain provides some perspective:

This incredible photo shows the cutting chain in action, ripping through the ship's thick steel:

Unfortunately, the chain actually broke during the cutting operation. "Approximately 25 hours into the cut, the cutting chain broke," St. Simons Incident Response writes on its website. Luckily, there were no injuries and there was no damage to the equipment. The team simply fixed the chain's broken link, inspected the other links for signs of fatigue, and continued on.

Here's another look at the cutting operation:

Here are a few zoomed-out shots of the severing chain in action. You can see the cutting chains for the next six cuts draped over top of the ship in the image directly below:

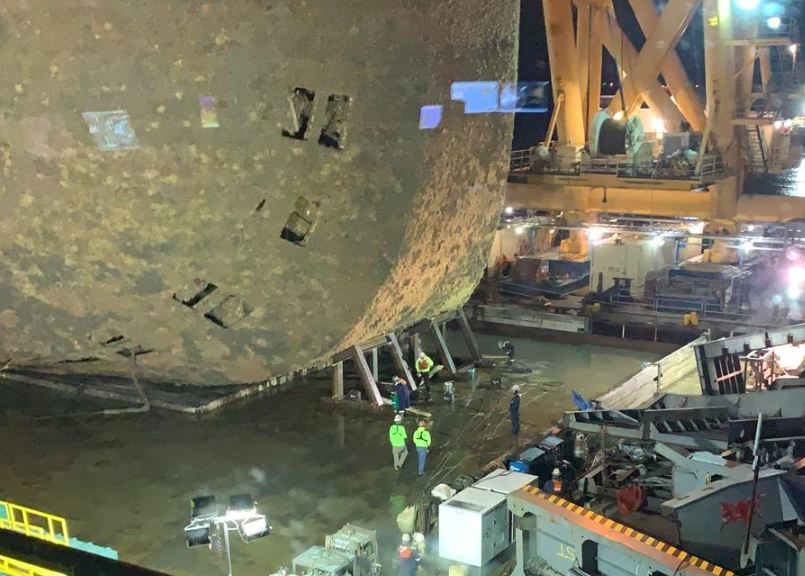

The resulting slice is impressive:

Here's a look at some workers guiding the chain out of the cut so that they can inspect the links. This is apparently standard procedure:

The photo below shows the cutting operation for the first section nearing completion:

Moving Section One Onto A Barge

The team completed the cutting operation on Saturday, and then used the VB-10000 to lift the section above the waterline:

From there, a barge named Julie B. and the VB-10000 both maneuvered into a specific position to allow the handoff of the enormous piece of shipwreck onto the scrap-carrying boat. You'll notice how the VB-10000 is well-removed from the rest of the wreckage:

Here's a look at the loading process:

The barge's deck is essentially flat, so to keep the ship section upright and stable, the team fastened the hulk to custom-fabricated "cradles" that match the hull's contours and that are tightly integrated into the barge's structure. You can see those cradles in black below:

The photo below shows some smaller cradles holding up the front of the chunk of car carrier ship:

Once fastened to the deck, the barged headed to the "East River" site near Brunswick so that the big chunk of ship could be further dismantled, and each bit secured for sea transport.

Barry Barteau, a local self-proclaimed "amateur photographer" took some incredible shots of the section of car carrier as it prepared for its final voyage to the scrapper:

The car carrier will eventually end up at a recycling facility in Louisiana, with St. Simons Sound Incident Response breaking it down, writing:

The bow and stern sections are more structurally sound and will be placed onto a barge inside the Environmental Protection Barrier (EPB). The barge will be stabilized and moved out of the EPB to a safe haven in Brunswick to go through sea fastening which is a robust process of preparing cut pieces to safely transit from the Brunswick area to Gibson, Louisiana some 1200 miles away.

[...]

The midbody sections that we have identified for partial dismantling will be secured inside the EPB and then transported to the East River site. Those sections will remain within a contained drydock to remove the vehicles. The pieces of the ship that remain will be secured to a barge and transported to Gibson, Louisiana. As we realize new or more effective ways to carry out our goals safely and successfully, we adapt our plan accordingly.

This part is interesting. Per a representative from St. Simons Incident Response, the front two sections and sections seven and eight will be removed in the way described above—VB-10000 will lift the sections onto a barge, the barge will then take the sections to a local facility to be cut up and fastened for sea travel to Louisiana. Sections three through six, though, aren't as structurally sound, so instead of the VB-10000 lifting them up onto a barge, a partially flooded "dry dock" will slide underneath the sections so that those sections don't have to be lifted as high (because, again, they're a bit floppy compared to the bow and stern). Then those sections will go to the local East River site, where the Louisiana scrap company has set up a temporary recycling facility, where the cars will be removed.

There Was A Lot More To The Operation, And Still More Ahead

This article is a far from an exhaustive look at the Golden Ray's removal operation. For one, I didn't even mention that the team extracted quite a bit of hardware prior to ever cutting the ship. The propellor and rudder, for example, went away last year:

In addition, the wreckage removal team cut apart and removed the 275-ton ramp that was used to load cars onto the ship. Workers did this, per St. Simons Sound Incident Response, as a way to reduce weight on the stern of the ship to make lifting easier for the VB-10000.

Another critical part of this whole endeavor involves environmental protection. It's not as exciting as cutting a ship into sections with a huge chain, but it's important and complex. The team in charge of removing the wrecked car carrier implemented an Environmental Protection Barrier or EPB. St. Simons Sound Incident Response breaks down the EPB on its website, writing:

The EPB will include large floating boom to help contain surface pollutants, as well as double layer netting to contain subsurface debris.

"We recognize that the floating boom of the EPB alone will probably not be enough to contain surface pollution when we cut into the hull," said Coast Guard Cmdr. Norm Witt, federal on scene coordinator for the response. "That's why we'll have crews and equipment, both inside the barrier and out, ready to respond."

In the FAQ section, the organization provides more details:

We anticipate that the Environmental Protection Barrier will not be 100% effective in catching the majority of oil and debris. The Environmental Protection Barrier has 28 nets that completely surround the Golden Ray each having a series of five-foot holes to allow marine life to safely move around while the nets are able to capture large debris which may be released from the Golden Ray. We regularly scan the sea floor with advanced technology so that any debris that escapes the barrier will be identified and targeted for removal. No single device or strategy is perfect, so we have multiple layers of defense and equipment positioned to mitigate projected threats to the environment.

Both passages above mention teams of people making sure pollution don't escape the EPB. The door panel below is an example of pollution that escaped the barrier, but that responders managed to recover:

All of this work and all of this time and seven of the eight sections of the Golden Ray car carrier remain. It's an incredible operation, but it's definitely not a quick one.

Update (Dec 3, 2020 10:15 A.M. ET): I asked a few follow-up questions to a Coast Guard representative. First, I inquired whether there exists a video of the cutting operation, and while he said there's nothing close-up, there is indeed a clip that includes audio of the cutting action. He noted that, at seven feet per minute, the chain appears stationary:

I also asked the spokesperson how the team went about snaking the chains under the ship. What I learned is that workers used what's called a "horizontal directional drilling system," or HDD for short.

"We basically took our cutting chains and they used this HDD technology to pass them under the mid-body of the Golden Ray," the public affairs specialist told me over the phone before mentioning that engineers first had to ensure that they had the right angles and profiles of the ship's hull relative to the surface of the sea floor.

Horizontal directional drilling is a commonly-used process that's often implemented to install pipelines. The video below describes how it works. The Coast Guard rep explained that contractors used the reamer—which, per the video below, acts to enlarge the bore after a pilot cutting tool has passed through—to pull a cable through the hole, with that cable being attached to the cutting chain:

I also asked the spokesperson about cost, and though he couldn't give me any figures, he said it's going to be extremely expensive. "We estimate that it will be the largest wreck removal in terms of cost in U.S. history," he said, also making it clear that "The cost of the response is fully backed by the ship's insurer."

I've also noted that the lift lugs used to hoist the ship's chopped-off section are steel, not iron as previously written.