Sleeving An Engine Block: The Pros And Cons Explained

Cylinders aren't the only feature that contribute to an engine's energetic output, but for good reason, they're the one we've settled on as shorthand. While it's just as accurate to say Corvettes have an eight-ignition coil LT2, cylinders are the metric we've all agreed upon. And why not? Cylinders have to bear immense pressure as pistons reciprocate through them thousands of times every minute, so they deserve the credit.

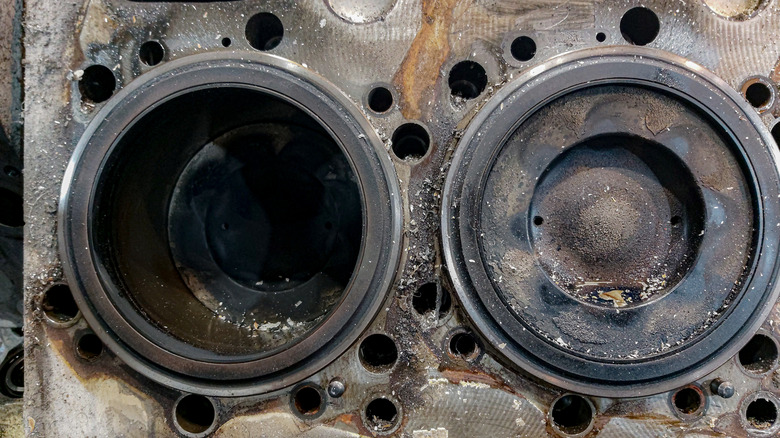

When cylinders get scored, worn, or pitted, they've earned the right to be freshened up for more miles of abuse, and there are three ways to go about it: One, bore the cylinders a hundredth of an inch or two larger (or more). Two, install cylinder sleeves or replace the existing ones. Three, get a whole new block, engine, or car. If you're a hot rodder who's boring over a Chevy small block to create a 383, that's a different story. The purpose there is to increase displacement rather than address cylinder wear, though it never hurts to get yourself some shiny new cylinder walls. Now, is sleeving or boring right for your block? That's a big "it depends."

This section will be boring

Aluminum blocks may not give you much choice, as there will likely already be sleeves in place intended for quick, easy replacement. Take Ed Donovan's revolutionary billet-aluminum 417 drag racing block, for example. With its wet sleeves (more on wet and dry sleeves later), racers could just swap the sleeves (also called liners) in a few minutes rather than rehone them. However, aluminum blocks with Nikasil- or Alusil-coated cylinders don't have it so easy. If there's cylinder wall damage, the coating has to be removed, often with nitric acid. Then the cylinders can be rebored and recoated or simply sleeved.

Let's address the pros and cons of boring first. If you want to increase your engine's cubic inches (or liters if you don't like freedom units), and the crank is already providing maximum stroke, then drilling out your cylinders for bigger pistons is your only path. With solid cast-iron blocks that don't require sleeves or liners as a matter of course because the material can handle piston ring wear quite well, you may be able to bore the cylinder out .010, .020, or .030 inches (the amount Joe Sherman bored his Chevy small blocks when creating the 383). Depending on the type of block, you might even be able to get away with more.

It'll cost you either way

Awesomely, boring is cheaper than sleeving. Advanced Racing Engines will bore your cylinders for around $50, while sleeves can be three times that, or more. Boring the cylinders also preserves originality for the block, too, if it's a collectible and that matters to you.

But the cost savings may come out in the wash. When you bore the cylinders, even just a hundredth of an inch, you're going to need new pistons and rings since piston-to-wall clearance needs to be precise. If you're sleeving an engine, you can get sleeves that are absolutely identical in size to your old ones and you might be able to reuse your pistons (with new rings, anyway), assuming they're still in spec.

Also, there's a decent chance that the boring process will eat into coolant passages, as happened to the Triumph Stag's V8 when going from 2.5 to 3 liters. If that happens, the cylinder will need a sleeve, anyway. Ultrasonic scanning can check whether there's enough material for boring, but that adds yet another expense.

Perhaps you should be sleeving

Engines are like shirts. Sometimes sleeves are necessary. In the case of engine blocks, this is less about being allowed into fancy restaurants, and more about preventing unfixable damage. Gas engines with aluminum blocks need Nikasil/Alusil coatings or cylinder sleeves lest the pistons grind away the walls. This goes double for aluminum-block high-horsepower diesels. With compression ratios often north of 20:1 , not to mention forced induction, the cylinder walls have to take black-hole levels of pressure. A durable heat-resistant cast-iron sleeve, flexible and shock-absorbing ductile iron sleeve, or strong and rigid steel sleeve can bear the brunt of the damage as well as handle the responsibility of maintaining bore geometry.

If you're wondering why sleeves are either "wet" or "dry," well, here's your explanation. Wet liners come into direct contact with coolant, while dry liners don't. Simple! As for which is better, that depends on what you want out of your engine. If staying cool and maintaining even temperatures are your ultimate goals, go wet, baby. If strength and rigidity are crucial, thinner dry liners leave more meat on the block. Sleeves can also be press-fit (aka interference-fit), which need final honing, or slip-fit, which are already finished and are ready for use.

Sleeves demand perfection, and will accept nothing less

Before adding sleeves, though, the block's cylinders need to be as perfect as possible lest the sleeves warp along with the block's distortions. Any shop doing the sleeving must take thermal expansion and conductivity into account, too. With the wrong size or material, the sleeves could pull away from the block. Since sleeving is expensive, you want it done right the first time.

Now, here's a benefit that you might not have seen coming: Sleeving an engine can even reduce displacement. Yes, limiting cubes is sometimes advantageous, perhaps to restore an original displacement or meet rules for a racing series. While more cubic inches certainly is desirable for those of us who want to make more power, consider a vintage engine that needs a cylinder repair because of deep scoring or plain old wear. If only one cylinder requires reconditioning, a sleeve can maintain the stock bore diameter, preventing the need for one slightly oversized piston. That will help preserve the engine's balance.

Yes, earlier, boring was extolled because it preserves originality, but the stock pistons would likely have to be chucked anyway when removing a thousandth or so from the cylinder wall. You have to choose what you want to keep original: the block or the pistons. You probably can't have both.