Why Metric And Imperial Horsepower Are Different

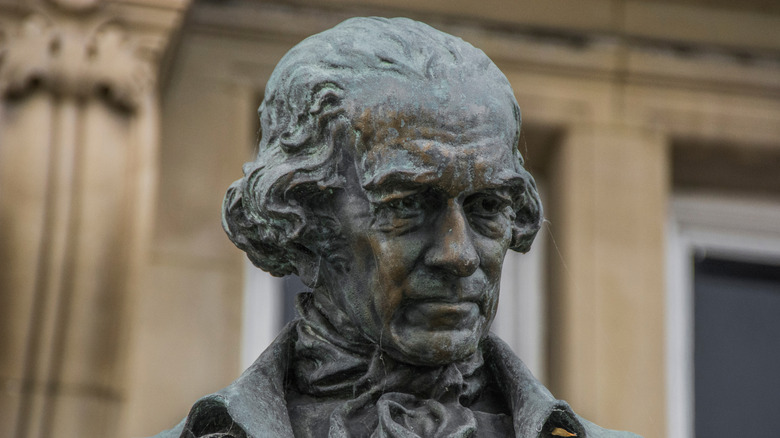

Blame it on timing. When James Watt gave the term horsepower an exact-ish definition in the 1780s, he actually borrowed the math behind it from one of Isaac Newton's assistants. It was John Desaguliers who, some 60 years before, worked out that it would take one horse exactly one minute to raise a weight of 27,500 pounds one foot off the ground. Watt didn't take the numbers for granted and believed 33,000 pounds was a more accurate measure, but he didn't mess with the idea that — mathematically — horsepower equals force multiplied by distance, with that total divided by time.

But the important part for our purposes is that he — being Scottish himself, like the self-driving bus that only needs two humans to operate — used the same traditional measures of pounds (for force) and feet (for distance) as common in the rest of Great Britain at the time. The metric system was a creation of the French Revolution and didn't become French law until 1795 – after Watt, but before the British Empire codified the Imperial system in 1824.

Now, to be sure, that doesn't affect the equation for horsepower, but changing the units does make a difference. When you plug in kilograms and meters for pounds and feet, you get one horsepower equals 75 kilograms of force per second versus the 550 pound-feet of force per second for Imperial horsepower. Something does get lost in the translation, though, so one Imperial horsepower is the equivalent of 0.986 metric ponies.

Gross vs. net horsepower

Horsepower can be measured in a number of other ways, too, but first a note from our hair-splitting department: Here in the United States we don't technically use the Imperial system of measurements. We use the U.S. Customary System that was formally introduced in 1832 — although they're pretty much the same except for measures of volume, like pints.

More significant is the difference in the non-math aspects of horsepower that are affected by how and where the measurements are made. For example, before 1972, automakers in the United States would often use gross horsepower when talking about their engines, giving them bigger numbers to boast about. That's because gross horsepower was measured with a bare engine that had been stripped of any possible power-sapping accessories, even components like water pumps, and had minimal exhaust restrictions. It made for great ad copy, but wasn't all that realistic because it didn't reflect how the engines were used out on the road.

To show that, the U.S. shifted to a form of net horsepower, with an engine set up to reflect more accurate driving conditions — and the results were dramatic. An extreme case is the Cadillac Eldorado that saw 165 ponies leave the barn when its V8 was de-rated from 400 gross horsepower to 235 net, and that's just one of the huge engines with surprisingly low horsepower from the time. The reduction was made even worse when folks compared the original gross horsepower number to net wheel horsepower, which we discuss next.

Brake vs. wheel horsepower

Before the 1970s, when the way automakers reported horsepower was legally mandated and, separately, an obscure British three-wheeled car became a Landspeeder, folks would try to differentiate ideal horsepower from real-world horsepower informally, by categorizing it as either brake horsepower or wheel horsepower. Brake horsepower, also known as crank horsepower, measured how much power was available at the crankshaft — the "brake" here referred to how the dynamometer applied a brake to the engine to measure its output by how much force it took to slow or stop the motor. It's kind of comparable to gross horsepower in that it doesn't consider power losses from anything downstream of the crank itself.

Wheel horsepower, as you might guess, is measured at the driving wheels with what's called a chassis dynamometer. It's the roller-type thing you may have seen in a speed shop or at a car show. With a chassis dyno, you're getting a measure of what horsepower remains after some of it is used to turn the driveshaft, differential, etc. Like net horsepower, wheel horsepower accounts for power losses, but more of them because net horsepower is still measured at the crankshaft.

Now, to circle back to the beginning, let's finish up by re-emphasizing that all these types of horsepower — brake, wheel, net, and gross — are distinguished by methods, not units. And units make the key difference between metric and Imperial horsepower no matter which method you use to get there.