Wreckage Of SS Western Reserve, Lost In 1892, Discovered In Lake Superior

We love a big boat, don't we, folks? From MV Evergiven to MV Mark W. Barker to good old MV Golden Ray, big boats are typically good for hours of family entertainment. Sometimes, however — especially if you have the honor of living in the Great Lakes Region — there's a darker side to messing around in boats. Somewhere between 6,000 and 10,000 shipwrecks litter Lakes Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, and Superior, and the lakes have claimed the lives of roughly 30,000 mariners and passengers since we started keeping records. While Lake Michigan has the most shipwrecks, and Lake Erie has the highest density, Lake Superior has, perhaps, the most famous.

There are nearly 600 vessels scattered across the bottom of Lake Superior, everything from nameless barges and tugs to the legendary Edmund Fitzgerald herself. The Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum is located on Whitefish Point — a spit of land every bit as dangerous as the Cape of Good Hope or Cape Horn — along Lake Superior's southern shore in Michigan's Upper Peninsula. There are nearly 200 shipwrecks within spitting distance of Whitefish Point, including the aforementioned Fitz. So many, in fact, that locals call it the "Graveyard of the Great Lakes".

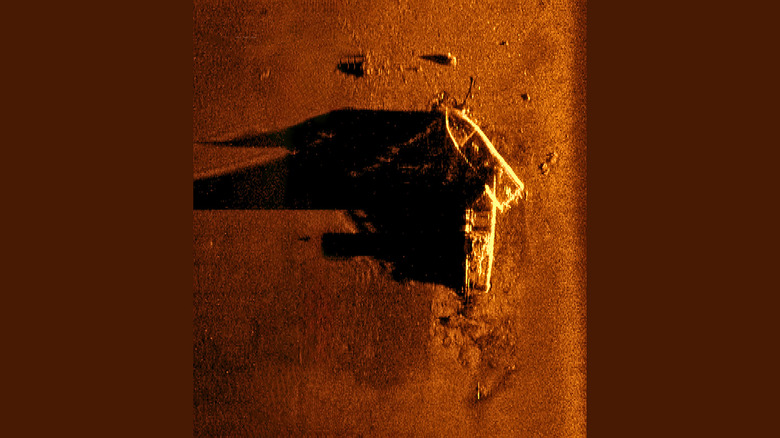

One of these long-lost vessels, SS Western Reserve, has eluded discovery since she disappeared in a late-summer gale in 1892. In 2024, however, Darryl Ertel — Director of Marine Operations at The Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society — discovered a wreck in 100 fathoms water some 60 miles northwest of Whitefish Point. It was a large vessel, broken in half with the bow section resting on the stern at a roughly 45-degree angle. At long last, the Western Reserve had been found.

The Inland Greyhound

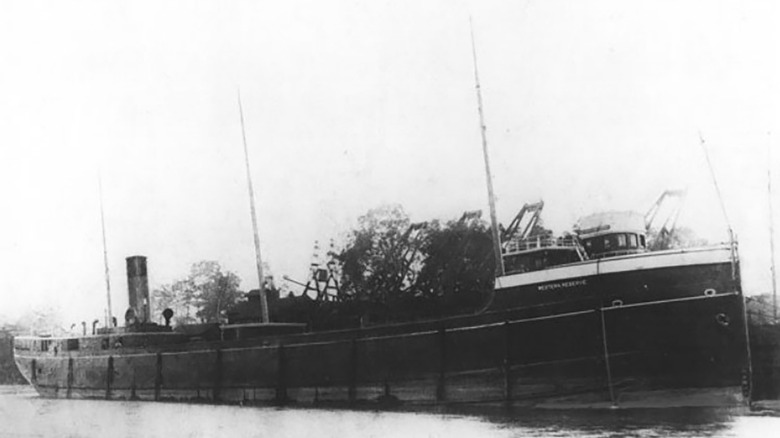

SS Western Reserve was laid down at the Cleveland Shipbuilding Company in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1890. One of the first ever lake propeller-driven lake freighters made entirely of steel plate, she was built for financier and shipping magnate Peter G. Minch's Minch Transportation Company. She was 301-feet long, 42-feet abeam, drew 21-feet of water, and had a crew of 26 officers and men. The ship's power plant was a thoroughly modern CSC triple-expansion steam engine that gave her a top speed around 12 knots, or 14 miles per hour. She was, by all accounts, a stout, fast, well-built ship that promised to revolutionize bulk shipping on the Great Lakes.

Built to break cargo shipping records, Western Reserve entered service in late 1890. For the next year and a half, the big vessel carried countless tons of bulk cargo—typically iron and other bulk ores—without incident. She quickly gained a reputation for speed and safety, and was nicknamed "the inland greyhound". Unfortunately, her career was cut tragically short when, in 1892, she was lost in a Lake Superior gale with only one survivor.

A Sudden Gale

In late August of 1892, SS Western Reserve set sail from Cleveland, Ohio, under the command of Captain Albert Myer. She was in ballast and headed for Two Harbors, Minnesota, to pick up a cargo of iron ore. Along with her officers and crew were embarked her owner, Peter G. Minch, and Minch's wife, children, sister-in-law, and his sister-in-law's daughter. The weather was fair, and everything looked fine for a late-summer cruise across Lake Superior.

By the time Western Reserve reached Whitefish Bay, however, the weather had started to turn rough. Captain Myer gave the order to drop anchor and wait out the weather. Eventually the winds died down, the ship weighed anchor, and they set off again toward Two Harbors. The lull in the weather was a fakeout, however, and the ship was hit by a massive squall at around 2100 hours that evening. She foundered in the heavy seas, and as Captain Myer gave the order to abandon ship, Western Reserve broke in two and sank.

Two lifeboats were launched, and all officers, crew, and passengers escaped the doomed ship. Sadly, one of the lifeboats capsized almost immediately. The other lifeboat, containing Minch, his family, and a handful of crewmen, rescued the two survivors from the capsized lifeboat and made its way into the eye of the storm. They were almost rescued in the night by a passing steamer, but without any flares aboard, the passing ship's lookout missed the tossing lifeboat.

The next morning around 0730, the lifeboat approached shore near the Deer Park Lifesaving Station, but rough surf capsized the boat less than a mile from shore. Only one person survived, Wheelsman Harry W. Stewart of Algonac, MI. The rest, including Minch and his family, drowned within sight of salvation.

Aftermath and Investigation

Western Reserve's foundering and the loss of her owner and his family sent shockwaves through the Great Lakes shipping industry and community. The disaster was even covered by the New York Times. At his post-rescue debriefing, Wheelsman Stewart's description of previously unreported metal fatigue throughout Western Reserve's hull and the rapidity with which she broke up suggested shady dealings on the part of Cleveland Shipbuilding.

An investigation turned up evidence that CSC had used steel contaminated with sulfur and phosphorus in Western Reserve's construction. The addition of those elements to the steel made it weak and brittle, unable to stand up to the constant abuse of the Great Lakes shipping season. Nearly two months later, SS W.H. Gilcher, a ship of comparable size and speed to Western Reserve, disappeared in northern Lake Michigan with the loss of all hands. Gilcher had been built at the same time as Western Reserve and with the same steel.

Outrage at the loss of both ships, a beloved ship's captain and his family, and the ensuing contaminated steel scandal led to serious changes in the laws governing what materials Great Lakes freighters could be built from.

Rediscovery and Closure

In late summer of 2024, the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society research vessel David Boyd, under command of Director of Marine Operations Darryl Ertel, discovered an unidentified wreck northeast of Whitefish Point.

"We (were) side-scan looking out a half mile per side and we caught an image on our port side," said Ertel in a story posted on the GLSHS website. "It was very small looking out that far, but I measured the shadow, and it came up about 40 feet. So we went back over the top of the ship and saw that it had cargo hatches, and it looked like it was broken in two, one half on top of the other and each half measured with the side scan 150 feet long and then we measured the width and it was right on so we knew that we'd found the Western Reserve."

Once the results of the Sonar scan were analyzed, GLSHS performed a handful of ROV (remotely operated vehicle, think a small, remote-controlled submarine covered in lights and cameras) missions to the wreck site. Researchers confirmed the identity of the wreck as the Western Reserve using the ship's known dimensions and the existence of some identifying artifacts including the vessel's bell, foremast, and port-side running light. The Western Reserve's starboard running light — the only artifact ever recovered from the ship — washed ashore not long after the disaster and is now on display at the National Museum of the Great Lakes in Toledo, Ohio.

Discovering a long-lost Great Lakes shipwreck is always satisfying, especially when it's one that researchers have been after for so long. It's also quite sobering, and a reminder of just how deadly the Great Lakes can be.

"Knowing how the 300-foot Western Reserve was caught in a storm this far from shore made a uneasy feeling in the back of my neck, a squall can come up unexpectedly...anywhere, and anytime."