How One Car Part's Journey To Production Shows Just How Interconnected The International Auto Industry Really Is...Or Was

President Trump announced new tariffs on Canada and Mexico, as well as China on Monday, sending the stock market plummeting. This morning, stock prices continued to fall, with the overall market only down a couple of percentage points, although certain individual stocks have fared worse. Tesla, for example, is down more than 10 percent since Monday's tariff announcement. Legacy automakers' stock prices dropped, as well, although not nearly as sharply as Tesla's. Unfortunately for everyone connected to the auto industry in any way, the complex, international supply chain it relies on leaves the auto sector uniquely exposed, the Wall Street Journal reports.

In fact, as the Journal put it, "no sector is as exposed as the automotive industry." To better understand just how exposed the auto industry is, they took a look at the journey a single part takes on its way to finally being installed in a car you can buy, as well as the myriad ways new tariffs will make producing that part even more expensive. Whether you're fully against or in favor of everything in the U.S. getting more expensive, it's a fascinating article, and I highly recommend giving the original a read, if only for the dynamic infographics they put together. If you don't have a Wall Street Journal subscription or are simply short on time, though, let's take a look at the highlights.

The scope of the problem

Before Trump's tariffs, about $1.6 trillion in goods and products traveled across U.S. borders with Canada and Mexico annually. That's also 30 percent higher than it was before Trump signed the renegotiated version of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 2018 that he insisted on giving a different name. NAFTA, meanwhile, had been in effect since 1992. That's only a couple of decades, but it's also been long enough that entire industries have organized themselves around the terms that were originally laid out. It also isn't like Ford buys one part that was fully produced in Mexico, another part that was made in Canada and then puts them on a truck in the U.S. As these parts are made, they often travel back and forth across international borders multiple times.

Depending on how Trump actually structures his new tariffs, we could see the prices of these vital components skyrocket if they're hit with a tariff every time they cross a border. And while it's possible to change suppliers to reduce tariff exposure, building new factories takes both time and money. Even if every company immediately moved to relocate its manufacturing to the U.S. and also figured out how to do that cost-effectively, it would likely be several years before consumers saw any benefits, leaving regular people with jobs and tight budgets to suffer as prices climb

Linamar

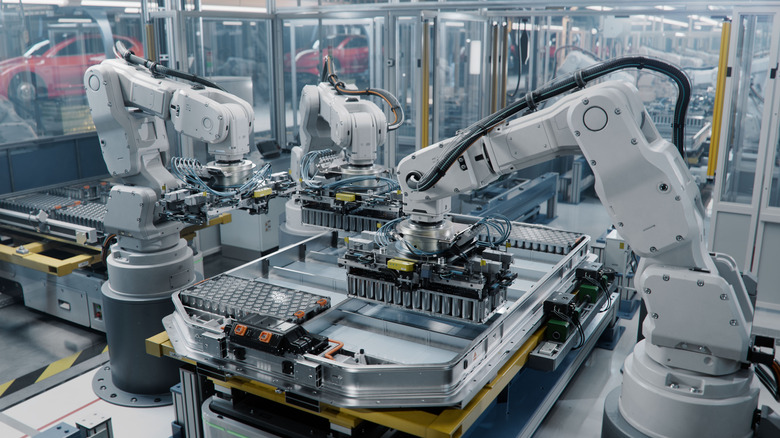

Take the Canadian supplier Linamar, for example. Linamar makes transmission modules for vehicles here in the U.S., and making those parts is far more of an international operation than you probably expected. Before Linamar even gets to making any products, it first needs steel to make them with. That means sourcing steel chips and scrap to be processed by a smelter in Pennsylvania. The resulting steel is then sent to Ohio where another company turns it into what's known as a hub. Once the hubs are finished, they're then sent to a factory in Ontario, Canada, along with another part involved in shifting gears that comes from Illinois. Before the module is complete, though, Linamar also imports an aluminum housing made in a foundry it operates in Coahuila, Mexico.

Once all the necessary parts are in Ontario, Linamar assembles the module and then sends it back to the Midwest where yet another factory installs it in the transmission. Those transmissions are then sent back to Ontario to be put into various vehicles that will then be sent to the U.S. for sale. If Linamar has to pay a tariff every time a part crosses an international border, those higher prices will compound, driving the cost of just the transmission through the roof. That may not be a problem for those of you who are rich, but that's bad news for regular working class people, especially in a country designed to make motor vehicle ownership a necessity.

The economic fallout is just beginning

Trump, of course, insists other countries will pay these tariffs, and before we know it, the U.S. will be so wealthy, we'll be able to simply get rid of the income tax. That's also, sadly, not how tariffs work, and you don't need a college degree to understand why. We're talking basic Intro To Economics-level "that's not how this works." Then again, when has Trump ever concerned himself with what's true or how things actually work?

In 2023, North America produced about 16 million vehicles, and according to the International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers, most of those vehicles used components that originated in all three countries. Trump's tariffs could easily add $10,000 to the cost of a new car, especially if it's made by Ford, General Motors or Stellantis, and those predictions aren't coming from purple-haired protesters or far-left college professors who just hate Trump. No, that prediction comes from Wall Street's S&P Global Ratings. If these tariffs were good for business, you'd think the folks at Standard & Poors would have found it. Instead, Trump just introduced a whole bunch of new inefficiencies into the system.

"There's been decades of investment, decades of each country developing what it's good at," Linda Hasenfratz, Linamar's executive chair, told the Wall Street Journal. "To try to now disassemble that is just going to drive a lot of cost and sacrifice." Ford CEO Jim Farley also expressed similar beliefs last month before the tariffs were announced, saying Trump's tariffs would add "a lot of cost and a lot of chaos" to its products if they went into effect.

Far-reaching effects

It would be nice if you could avoid the negative effects of Trump's tariffs by simply not buying a new car until he's no longer in office, but sadly, that isn't really an option. If anything on your car breaks, tariffs will also drive up the cost of replacement parts. On top of that, higher new car prices will also push more people to buy used, driving up the cost of used cars as well. Don't be surprised if the chaos and high prices that kicked off when the pandemic broke out during Trump's first presidency. And that's before you throw the new measles outbreaks into the mix, as well as the ever-increasing threat of bird flu. If auto workers start getting sick, that could also impact production speed, further reducing the supply of new cars and driving up prices.

If our country had been better-developed with people in mind instead of parking for cars, good public transportation and walkability would make it easier to temporarily opt out of car ownership for a few years and keep a motorcycle around for fun. Since that isn't the case, though, we may just have to grin and bear it until enough people get mad enough about the higher cost of living to throw these billionaires out on the street and put someone serious in charge.

And that's even before we get to the number of jobs that will likely be lost as prices go up, consumers buy fewer goods and services, and companies close down. The hundreds of thousands of federal workers and contractors who have just lost or are about to lose their jobs were already going to be bad enough for the unemployment rate and the economy at large without Trump sending consumer prices through the roof. Apparently, though, being worried about working families struggling to pay the bills and being buried in debt is un-American now. So that's nice.