The Rise And Fall Of Studebaker: What Went Wrong?

Even the gorgeous, if a bit esoteric, design work of American greats Virgil Exner, Brooks Stevens and Raymond Loewy couldn't save Studebaker from its slow-but-inevitable post-WWII collapse. The South Bend, Indiana-based manufacturer started life as a horse-drawn coachbuilder in 1852, and just 114 years later it completely disappeared from the face of American manufacturing. With a focus on quality, durability, and reliability, Studebaker was once a major player in the U.S. automotive industry. It had a history of building sharp designs and powerful engines, but as a smaller independent brand it just couldn't keep pace with the development curve and economies of scale that companies like Ford and General Motors enjoyed. Where the Big Three could make incremental annual improvements on its designs and powertrains, Studebaker had to take big swings on design in order to make its outdated chassis and powerplants appealing.

Studebaker was heavily subsidized by military contracts during WWII, building aircraft engines and trucks that helped propel the Allies to victory. The company was pretty forward thinking, and used some of those wartime financial gains to prepare for a world after the war ended. Studebaker made major concessions with its unionized workforce to prevent the strikes that plagued the Big Three in the post-war era, and invested heavily in its 1947 lineup. The company shouted about the new lineup in advertisements reading "First by far with a post-war car" pushing the new Starlight coupe.

Post-war slump and merger

Despite a successful re-launch after World War II, Studebaker quickly found itself swallowed up by the traction that Big Three brands found. Studebaker sold around 400,000 vehicles in 1950, riding the wave of post-war American largesse and attractive new Champion and Commander designs. Once Ford, GM, and Chrysler got back on their feet and replaced aging designs with new post-war machines, Studebaker's advantage evaporated. By 1954 the company's sales declined to just 100,000 units and suffered a $26 million deficit. Henry Ford "The Deuce" and his beancounter Whiz Kids changed the world of automotive manufacturing and kicked off a pricing war between the Blue Oval and the General in the mid 1950s, a war that Studebaker just couldn't fight.

A merger was proposed between Studebaker, Packard, Hudson, and Nash to help all four of the smaller American automakers weather the storm, but the details couldn't be hammered out. Hudson and Nash merged on their own to become American Motors Corporation, while Studebaker and Packard struck a deal to join together. Then-UAW representative Lester Fox likened the merger to "two drunks trying to help each other across the street." By the late 1950s the company was in dire straits with poor quality control, an aging lineup, and the highest paid workforce in the industry. While Ford and GM were more than happy to weather a UAW strike, Studebaker continued paying its workers better and providing more benefits to prevent costly downtime and product delays. Unfortunately, this meant that Studebaker simply could not price its cars any lower than it already had, and was losing what little market share it owned to cheaper Big Three machines. By 1958 the combined Studebaker-Packard company produced just 56,920 units.

A new president and new ideas

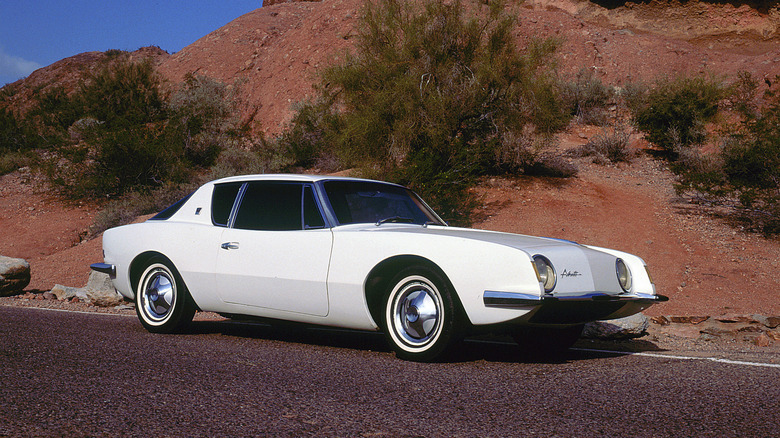

In 1961 the company's new President, Sherwood Egbert, sought to reinvent the company with an increased focus on quality and design. He ordered the company to spend millions of dollars it didn't have to remodel its factories and gave Brooks Stevens just six months to facelift the company's compact and midsized Lark and Hawk models. Egbert's biggest swing, however, was investing in a new high-performance halo car for the brand. Egbert hired designer Raymond Loewy and gave him just six weeks and total autonomy to develop a work of art. That's how the now-iconic Studebaker Avanti was born. A fiberglass-bodied V8-powered ground-pounding street machine that looked exactly as futuristic as it should. Once the design had been finalized, it was up to the engineering team to make it a functional car. Egbert allegedly told engineering chief Gene Hardig that the Avanti "must be tops in speed, braking, handling, safety features, and general innovation—and please don't spend any money."

Wrong turn ahead

Studebaker/Packard had heavily invested in diversification through the 1950s and owned the Paxton supercharger company, so it offered an incredible 300-horsepower supercharged version of the Avanti. It was also the first mainstream American car to be fitted with disc brakes. This was a seriously powerful car for the early 1960s, and practically invented the concept of American Grand Touring. Ten prototypes were built for 1962 ahead of the Avanti's production run in 1963. Studebaker gave Avantis to Jimmy Dean, Dick Van Dyke, Johnny Carson, and Frank Sinatra in an effort to influence the public on the car's cool appeal.

Unfortunately the big gamble came up bust for Studebaker. A lengthy labor strike in 1962 set the company on the back foot, and continued quality concerns did the rest of the work. The Avanti used advanced fiberglass manufacturing procedures that Studebaker workers just weren't prepared for. The designers didn't account for the components shrinking during the curing process, and as a result nothing fit together right, and the rear windows developed a nasty habit of popping out at speed.

A shorten tenure

Egbert was removed as President of the company in December of 1963 after it became obvious that initial sales of 1964 models was falling short of expectations. In a last gasp effort to keep the company afloat, the board closed the company's aging South Bend plant with the final Larks and Hawks produced on December 20 and the final Avanti, a high-performance R3 model, produced on December 26. The facility continued making postal vans until early 1964 to fulfill its government contracts. The company's limited production capacity was consolidated to its last remaining facility, the Hamilton, Ontario plant. New president Gordon Grundy oversaw the operations of the company in its death throes. Avanti tooling was sold off and continued as its own brand for several decades. The design of the company's Champ truck were sold off to Kaiser Jeep, as well as the South Bend plant, where Kaiser Jeep built military vehicles for a time. For 1965 Studebaker produced just shy of 20,000 automobiles, and wasn't anywhere near break even. Grundy flew to Japan that year to discuss selling imported Nissan Cedric and Toyota Century models as Studebakers with help from then-former United States Vice President Richard Milhouse Nixon. Toyota got wind that it was Studebaker's second choice and backed out of negotiations with Grundy, which made Nissan aware that Grundy had talked to Toyota and also ended the relationship prematurely out of disgust.

The end

The board decided that it couldn't reach profitability in an appropriate timeline, and declined to invest more in the automobile business. Studebaker exited the automobile business altogether in March of 1966. By that point the company's engine foundry had ceased operations, and when it ran out of its own engines, purchased a few General Motors engines to finish out production until dealer contracts were fulfilled. By May of the following year Studebaker and its diversified holdings (which by then included an airline, a refrigerator manufacturer, STP chemicals, and a missile division) were merged with Wagner Electric, and the conglomerate later merged again with Worthington in November of the same year. Once a major player in the American auto industry, Studebaker died a slow and sad death, crushed under the weight of manufacturing powerhouses Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler.