Not Every Airport Needs Air Traffic Control

It's safe to say that America has an air traffic control problem. A lengthy string of near-misses culminated in the worst possible outcome last month: a fatal mid-air collision between a regional jet and a military helicopter at Reagan National Airport. Despite the federal operational dilemma, most airports nationwide operate without on-site air traffic control. However, these places are far from lawless due to procedures regulated by the Federal Aviation Administration and supplemental information specified by each airport.

I should clarify that the most common kind of airport isn't the one you're likely familiar with as a commercial airline passenger. According to the Air Safety Institute, around 500 airports have ATC towers, while there are nearly 20,000 non-towered airports. These are typically general aviation airports handling small turboprop planes. While these airfields are also called uncontrolled airports, certain institutions prefer the term 'non-towered' to allude to rules that maintain order.

The right of way in the sky

As with cars on the road or boats on the water, there are right-of-way rules. Most importantly, an aircraft in distress always has the right-of-way. Unpowered aircraft, like balloons and gliders, are next in order of precedence ahead of powered planes. Planes on final approach for landing are placed above all other planes in the sky or on the ground. Between flying planes, the aircraft on the right has the right-of-way. Planes overtaking or approaching head-on are also expected to pass or turn away to the right. It's reasonably straightforward.

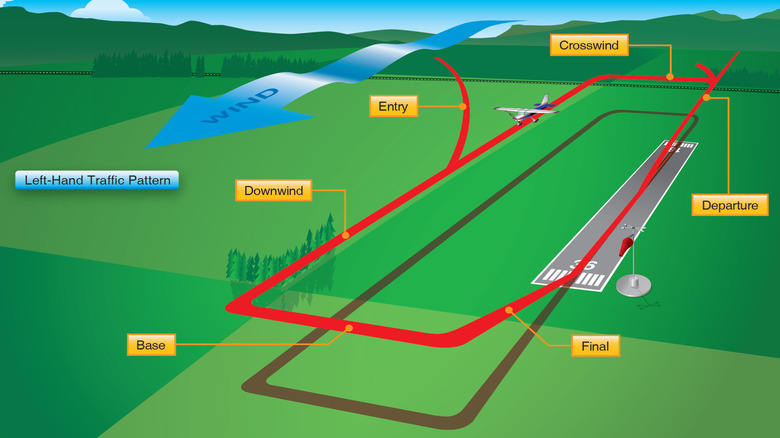

Landing is slightly more complex. The regulations are malleable and local management adapts them to each airport's particularities. The standard traffic pattern is a basic building block for non-towered operations and can be visualized as a six-leg box. The runway forms one side of the box but features two legs, departure and final approach. Two legs run perpendicularly ahead and behind the runway, the base and crosswind legs. Departing planes can fly straight ahead to leave the pattern or make a 90-degree turn to stay in it. Planes are always required to fly in the same direction.

Continuing the pattern, the downwind leg is parallel to the runway but with traffic flying in the opposite direction. The segment connects the crosswind leg with the base leg. The sixth and final segment is the upwind leg, parallel to the runway, with planes flying in the same direction but a safe distance away.

Pilots still communicate without air traffic control

Visibility is the biggest danger for pilots approaching and departing non-towered airports. According to the FAA, only two percent of mid-air collisions happen at night, at dusk, or at dawn. Planes covered in lights are easier to spot at night. To help everyone stay aware of who's where, pilots are also required to tune their radio to the common traffic advisory frequency (CTAF) and announce their position in pattern.

This type of airport operation is only possible due to the low volume of traffic. It would also be impossible to staff every airport across the country with controllers. The FAA is struggling to staff the facilities that absolutely need ATC personnel. The fact that only a fraction of airports have towers illustrated how thinly stretched air traffic controllers are. It's not surprising that many can't deal with the stress, falling asleep on the job or showing up to work drunk.