How Science Fiction Failed Us: The Real Future Of Autonomous Cars

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Elon Musk believes in it. So does Uber's Travis Kalanick. The Autonomotive Singularity is inevitable. It is the enemy of enthusiast car culture as it stands, but only as we know it. If we come to understand it, it might just be the best thing ever for car enthusiasts. Might.

I'm interested in the future of driving itself, which is why I lie in bed at night wondering if Elon Musk is right.

If you truly love driving, you need to understand the Autonomotive Singularity, and that means you have to stop ignoring it and accept it.

What is the Autonomotive Singularity?

The Autonomotive Singularity is the idea that human input is the weakest link in the transportation chain, manifested to its logical end. It is Uber meets Skynet. It is the sun around which every digital automotive "advancement" currently orbits.

These comprise everything car enthusiasts claim to hate. Traction control. Lane Control. Stability Control. Automatic Braking. Steering-by-wire. And of course — the final enemy — Autonomous Driving (or AD). The latter is the glue that bonds these technologies together, and it will harden, inexorably, as legal and technological barriers are crossed, until some combination of economic, cultural and psychological factors remove steering wheels from cars altogether.

Mercedes’ autonomous F015 concept.

Sure, there will still be some human-operated cars on the road, somewhere, much like there are still pack animals in use and even horses ridden for pleasure, but the center of transportation-related gravity will shift. To paraphrase Winston Churchill, it is the beginning of the beginning. Anyone who doesn't see this isn't thinking past the end of the beginning.

The end of the beginning will happen in our lifetimes, and the Autonomotive Singularity will follow.

Why don't people who "love driving" see this? In part, because science fiction has failed us.

Science Fiction Left Us Unprepared

I'm a huge fan of science fiction. Not the pop culture trash passed off as science fiction. I like real sci-fi, which is rarely what you find on the Syfy channel. Most people can't tell the difference, so here are two simple tests. First, if it's misspelled, even deliberately, like Terminator Genisys, it's not science fiction. Second, if it contains designs by Syd Mead, it's probably sci-fi. Possibly, but not necessarily. The time-traveling armchair from Timecop? Not sci-fi. The "spinners" from Blade Runner? Sci-fi.

It isn't the presence of flying police cars that makes Blade Runner sci-fi. Space travel, megastructures, off-world colonies; these multiple technologies serve as context to the story of one technology in that film — genetic engineering — and the unintended consequences it brings upon people. People who seem very much like us. That notion of our own reality meeting the inevitability of our own actions is is the heart of the very best science fiction.

Now consider this: androids, sentient robots or artificial humans are decades away, at least, and yet the definitive and most educational film on the moral, ethical, social, and political consequences of their creation will have been made in 1981. Thirty-four years ago. The day the first replicant acts out, no one will be able to say we weren't warned.

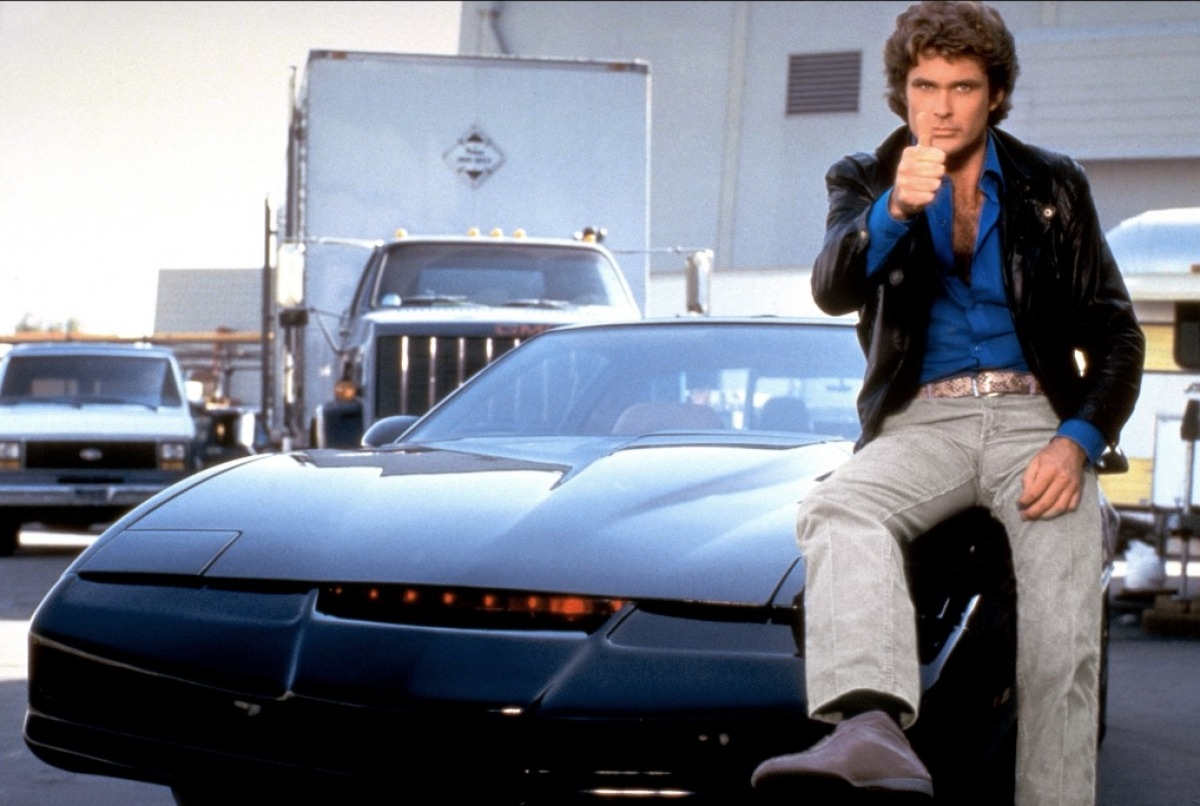

If, as Mead once said, science fiction really is "reality ahead of schedule," then car enthusiasts have a problem, because the most popular depiction of AD ever is Knight Rider.

Yes. Knight Rider. Which ran from 1982 to 1986.

Now I love Knight Rider as much as the next 12-year old did in 1983, but Knight Rider is to autonomous driving as Hackers is to the actual internet. Or is it? After re-watching several episodes, I'm convinced it might be absolute genius. Knight Rider predicted virtually every AD headline in recent months 30 years ago.

Car hacking? KITT gets hacked. Cars want to have free will? Meet its evil counterpart, KARR. Remote car disabling? KITT does it in almost every episode. It only took a few hours of viewing to realize why Knight Rider is not yet seen as the seminal work on AD.

Knight Rider was set in the present. The present of the early '80s.

Had Knight Rider occurred in the near future, in a world where AD is taken for granted, and KITT and/or KARR been the first to achieve and transcend full AD, and had we seen the consequences of AD – cultural, economic and personal – to relatable characters, then we might have had the Blade Runner of cars, and none of the recent headlines about Fiat Chrysler hacking would have been a surprise.

In other words, we never got a vision of the future better than Knight Rider, so we find ourselves unprepared.

In the absence of good science fiction on the topic, who is actually discussing AD in a meaningful way? No one is doing so publicly, although the private discussions can be gleaned by perusing venture capital and tech industry newsletters. The mainstream media and most auto journalists don't have much of a clue either. They treat AD as the first, non-speaking iteration of KITT, in a meaningless vacuum. The sum total analysis of the consequences can be found in the last few lines of pretty much every article on the subject:

"Big changes are coming." But no one, not the industry, not the media, and not consumers, has their eye on the endgame.

The Bad News For Driving Enthusiasts (For Now)

Lacking an anti-AD sci-fi epic as a rallying cry, people who "love driving" have buried their heads in the sand, hoping it will never work, or that widespread deployment is so far off they'll be dead and therefore doesn't matter.

It does matter, because between the end of the beginning and the Autonomotive Singularity enthusiasts will find it increasingly frustrating and costly to share our declining infrastructure with AD vehicles. Whether enthusiast culture evolves or dies depends on whether we recognize and adapt to these changes.

Big changes are made of myriad little ones. AD already exists, in pieces and projects, unfolding at varying speeds all around us, and yet legacy manufacturers have already ceded territory in EV, mapping and on-demand services to new players like Tesla, Google, Uber, and Apple.

Enthusiasts can talk about passion until they're blue in the face, and yet can't organize beyond the next Cars & Coffee, let alone be bothered to join their local SCCA chapter.

Meanwhile, the current Tesla Model S is one law and one over-the-air software update away from driving itself from New York to Los Angeles.

Driving as a privilege will evaporate as we know it, in time, as technology and market forces converge at an increasing pace, unless we stop talking about AD as it pertains to cars and begin discussing its effect on people.

Do not take this to mean I am a defeatist on the future of human-operated vehicles. I am not. As one of the fans of Brock Yates who actually put my money where my mouth is, I dream of road-tripping in my Citroën SM with my unborn grandson. My faith in technology and reason stands utterly at odds with that dream. I also don't want to see my wife hit by a drunk driver. And so I've struggled with the unspoken reality facing all car enthusiasts:

AD will save lives. The best driver might make a mistake. The worst ones eventually will. The Autonomotive Singularity will resolve that problem.

That's bad news for car enthusiasts – on an individual level – in the near and mid-term. But it's also very good news for us as a community in the long-term. It's just going to take time to get there. And by some time, I mean a long time. I hope I live long enough to see it. I doubt I will.

Now let's deconstruct the other side, flying the banner of what let's call the...

The Automotive Singularity

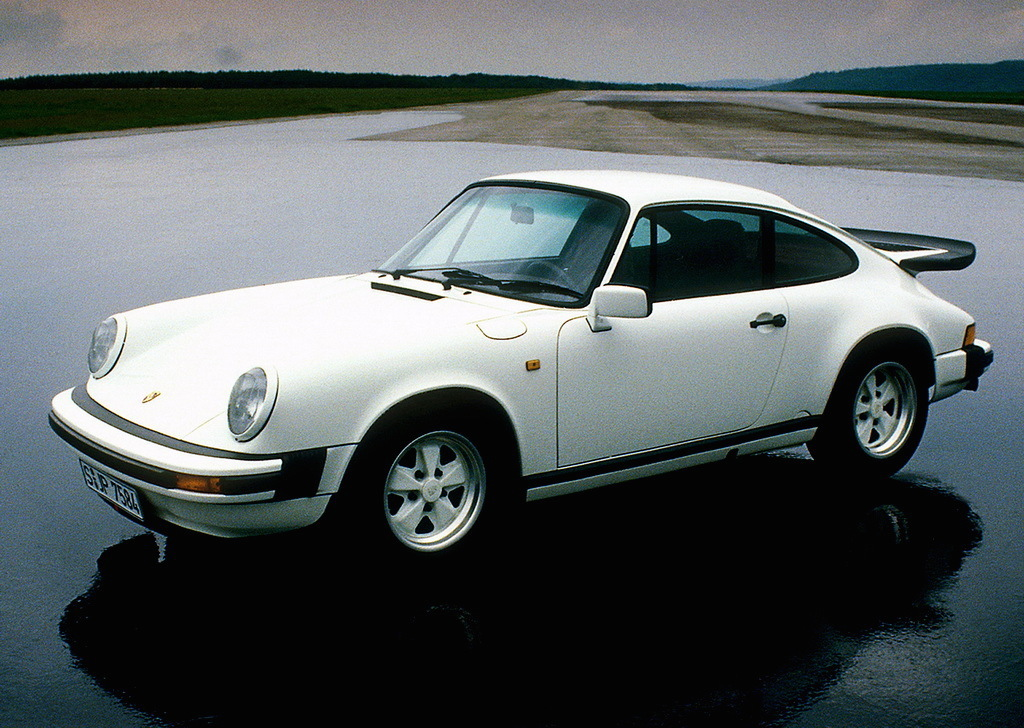

The Automotive Singularity (not the Autonomotive Singularity, mind you), was an era approximately 20 years in length that ended around the early 2000s. This era is characterized by "modern analog" cars, whose increasing popularity today is not merely due to nostalgia. It was during this period that vehicular performance and control feedback reached an equilibrium, prior to the widespread adoption of electronic driver aids, safety systems and GPS.

This equilibrium point varied across makes and models. The 1987-89 Porsche 911 is a perfect example of an equilibrium car. Quick, balanced, light, somewhat dangerous at the limit, and unquantifiably more satisfying than most modern vehicles. A modern Camry may be quantitatively superior than that old 911, a Honda minivan may be quicker in a straight line than a Ferrari 328, and yet we yearn for cars whose appeal cannot be measured this way.

But it can be measured. Intellectually. Conceptually.

The Automotive Singularity was the period during which the driver-to-driving relationship was at its analog apex and digital nadir. The maximization of the driver's connectedness to the act of driving was inversely correlated not only to the level of electronics in-car, but to the volume of data available through increasingly complex displays and handheld devices.

As the price of performance continued to fall, the average car's capabilities began to greatly exceed that of the average driver, not to mention most road infrastructure. As driver aids, safety systems and electronics became interdependent and ubiquitous, the average driver's ability to understand and maintain their vehicles evaporated. As traffic and weather data, navigation and iPod/iPhone integration grew ubiquitous, the relationship of driver to driving, of driver to destination, of driver to passenger, of driver to other drivers, were all irrevocably changed.

Isolation as escape. Driving as catharsis. The uncertainty of an ETA. The opportunities inherent to getting lost. The adventure of the road trip. All gone. Not literally, but conceptually. Intellectually. The very freedoms such new technologies grant us also take something away. How can it be otherwise, when most people under 30 don't understand what it's like not to have the option of GPS?

Drivers can turn off these devices and regain the freedom to be free, to be independent, to not know, to learn instead of to be told and to lead instead of to be led, but they cannot escape knowing that, at any moment, their isolation is a toggle switch or app away.

The last drivers to understand this have already been born.

And so this era, which I believe will be seen as the Silver Age of the Automobile, came to an end.

But there is hope for enthusiasts.

When Will The Autonomotive Singularity Occur?

"On a long enough timeline, the survival rate for everyone drops to zero." – Chuck Palahniuk, Fight Club

The Autonomotive Singularity will occur the day the last person gets in a car and leaves his or her driveway, having relinquished all input other than destination.

Whatever one's views on AD, two facts are indisputable. AD will be 1) safer, and 2) more convenient than Human Driving (HD). We can debate the definitions of safety and convenience, but not their merits. This debate will ultimately be overtaken and won by market forces driven by demand for these, whatever the definition, once costs have come down. Following the logical tree, AD, on public roads, as the dominant mode of transportation, is inevitable.

In other words, on a long enough timeline, the survival rate of human-operated transportation culture drops to zero.

There is no meaningful debate to be had over the length of the timeline, because even if enthusiasts don't believe AD is inevitable, auto manufacturers and the tech industry do. The center of investment gravity has already coalesced around this belief. Technologies developed in parallel have begun to converge.

From the automotive side, the individual components of AD – automatic braking, distance-sensing cruise control and steering – have begun trickling down product ranges. They started on luxury cars and are now standard across the entire Volkswagen lineup.

From the tech side, navigation systems incorporating real-time, organically-generated traffic data are improving at an accelerating rate, and platforms such as Uber are — local political hurdles notwithstanding — becoming increasingly ubiquitous. Right now it's an app to hail a ride, but that's just for right now. And where Uber stalls, a competitor will rise. You think nature always finds a way? Business does that even better.

The ultimate convergence of these interests guarantees the arrival of the Autonomotive Singularity.

Technologically, this is feasible in our lifetimes. Culturally, politically, legally, socially, it's going to take a lot longer.

How long? Let's go back to Knight Rider, which is what I call "single-vector science fiction." Single vector stories pre-suppose the deployment of a new technology in a vacuum. All external factors are ignored. All secondary consequences are omitted to meet time or page limits. It is the laziest of all science fiction. Knight Rider is a pretty good example of it, and because it didn't look too far forward, it got some big things right.

If we project AD forward on its own – in a vacuum – about 75 to 100 years, we can posit three phases.

The first phase will see legal barriers to AD fall. The successful deployment of AD by on-demand services like Uber, the military and trucking companies will lead to cultural acceptance. A psychological shift will occur as full AD vehicles are seen as mobility appliances, evolve separate nomenclature, and begin to supplant traditional carpooling and ownership solely for commuting purposes. HD will become safer and, initially, slower. Motorcycles will rise in popularity.

The second phase will be dominated by conflict between "AD Transportation Culture" and "Driving Culture." Human drivers will bristle against rising insurance premiums, the conversion of HOV lanes to AD, and the slowing of traffic as flow stabilizes to match our already artificially low speed limits. Anti-AD road rage will peak. The rise of AD will reduce municipal revenues derived from fines, which will lead to increased fines upon a declining pool of human drivers. Political and cultural pressure will grow to regulate, diminish and even prohibit human driving, first for pleasure, then for work...geographic requirements notwithstanding.

The third phase will see AD pass the tipping point. Investment in AD-specific infrastructure and widespread improvements in efficiency and quality-of-life due to an "AD Network Effect," which will occur once deployment reaches a critical mass. Anti-HD laws will likely go into effect.

Where they don't, HD will be shunned. Impossible? Draconian? The French have already taken steps to ban cars of a certain age in Paris. In London, congestion charges are levied against vehicles by size and time of day.

But there is the good news for enthusiasts. Maybe even great news. Patience will be necessary.

Why The Future Won’t Suck For Enthusiasts Eventually

You don't need to be Nostradamus to know events will unfold differently, because real life resembles the multi-vector science fiction exemplified by Blade Runner. Musk, Kalanick and countless AD engineers around the world aren't working in a vacuum.

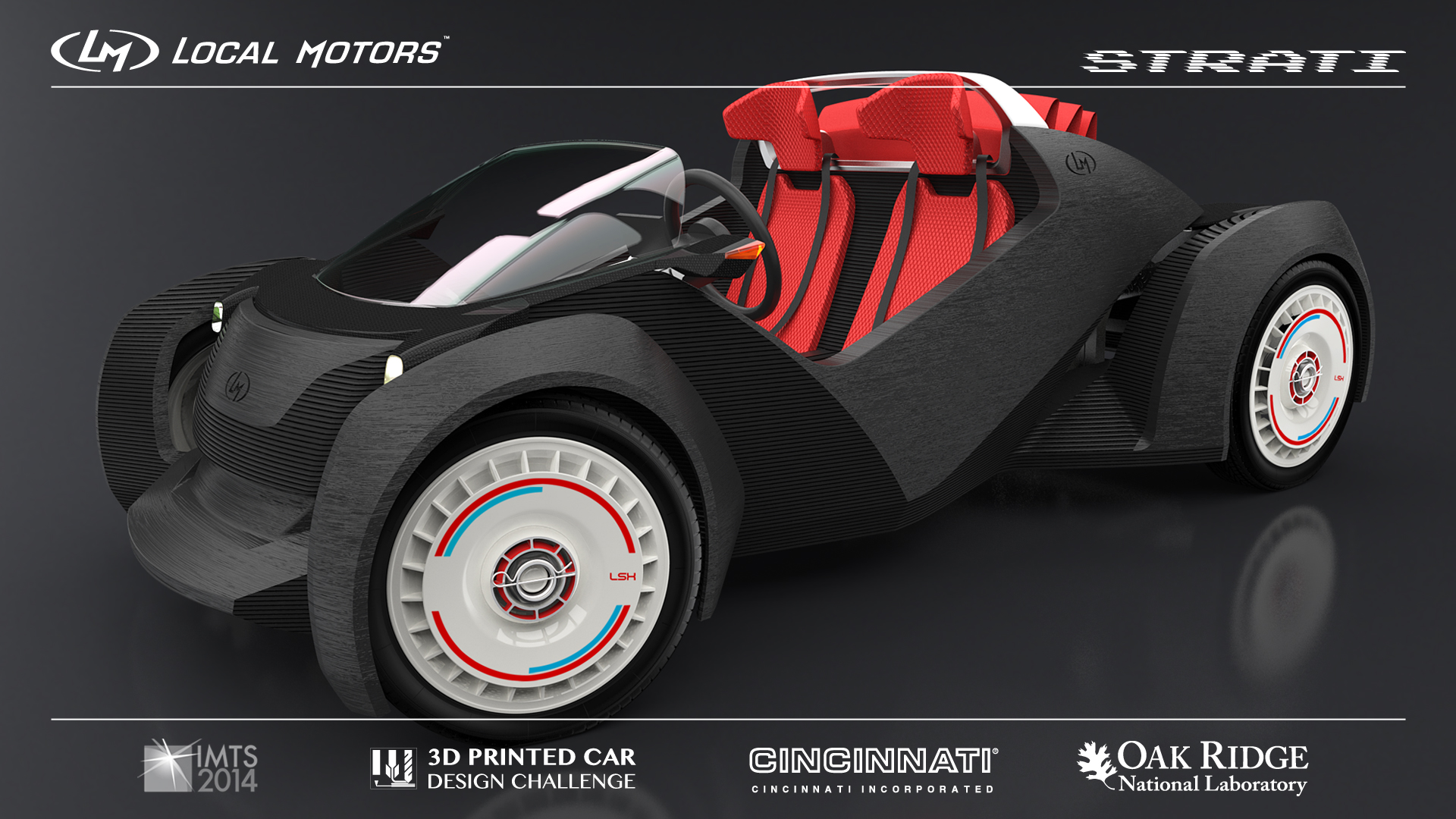

Consider all the advances likely to parallel and converge with AD – advances in 3D printing, material science, virtual reality, optics, aerospace and nanotech – and the second and third phases on the path to the Autonomotive Singularity begin to look very different. The Singularity won't just be the end of the car culture as we know it, but also the catalyst for a radically new and almost certainly more exciting stage for enthusiasts.

A greater proportion of today's population has driven a car than – only 100 years ago – had ever ridden a horse. For the majority who'd never owned one, the arrival of the automotive age was not merely a transition from one mode of transportation to another. It was a shift from near zero mobility to infinite mobility.

The car transformed the definition of freedom, annihilating geographic, social and cultural barriers, and came to embody freedom itself. The car has became the object onto which people project their ambitions, and onto which they pin decisions and memories that amplify and reflect who they are. Where a home cannot go, a car can. It is a safe haven we bring with us. A car changes simply by our sitting in it, before we've left the driveway, and changes us by where we go.

Although technology has begun to dilute our relationship to driving, it cannot dilute our relationship to the vehicle, both literal and figurative, that takes us where we choose to go, not just because it can, but because it's ours. Enthusiasts love cars not merely because of what they are, but because they are an extension of the self.

Cultural memory is long. Very long. This is a far greater part of the fabric of our culture than the Autonomotive Singularity can ever wash out.

On the contrary. For every AD vehicle deployed, demand for pre-AD vehicles will rise, but ownership of the latter will become inconvenient, costly, and largely untenable for all but the one percenters for whom driving will follow the show horse metaphor. But, where there is demand, there will be supply, once seemingly disparate technologies converge to meet it.

The cultural memory of what pre-AD cars represent – to what driving actually means – will lead to myriad opportunities for investors and drivers yet unborn to meet. The Model T is as alien to us as any car of today will seem fifty years from now. Imagine a perfect cosmetic replica of a 1977 911 Turbo, with 3D-printed nanotech panels and a flexible cage, with feedback systems perfectly mimicking the original.

For those who choose to drive, the back roads of the future could be a playground

Large swaths of the American West remain devoid of traffic even today. Imagine a future with on-demand road availability, with pre-reserved stages where HD car rallies pass not annually, but monthly, even weekly, so great is demand.

The country is littered with amusement parks and racetracks left to rot. Compared to Disney or Legoland, the current state of racetrack facilities is pathetic. Imagine a future where every major city is blessed with an evolution of Ferrari World crossed with a mechanical zoo. Where VR-trained kids can visit MustangWorld or SpeedLand, get into an AMG Hammer or Miata Spec replicar, get a license and race under safe conditions. Any one of these scenarios will lead – for those who still seek a driver's license – to higher average skill levels than we have today.

Car culture will fracture and proliferate everywhere driving is mythologized, and with it, choices.

It is therefore in the interest of all enthusiasts to speed the arrival of the Autonomotive Singularity, such that we can weigh in on what follows it. No matter what we drive, the better we do it, the safer we do it, the more likely the cultural memory of driving will be served by the future rather than smothered by it.

I also recommend buying every decent condition pre-2000 sports car you can get your hands on. You never know what's going to happen.

Alex Roy is the founder of Team Polizei, a host on /DRIVE, author of The Driver, President of Europe By Car, Producer of The Great Chicken Wing Hunt & 32 Hours 7 Minutes, was Chairman of The Moth from 2002-2007, won The Ultimate Playboy on Sky One, has competed in LeMons & the Baja 1000, and holds a variety of driving records, most notably the 2006 NY-LA Transcontinental Driving Record, accomplished in 31 hours and 4 minutes.

You may follow him on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Top Graphic credit Sam Woolley

Photos credit Mercedes-Benz, Porsche, Trent Landreth, Local Motors